The Grunge Pilgrimage

/Growing up as the younger brother, I was exposed to whatever my older sibling listened to as he was coming of age in the early ‘90s. MTV still had music (who remembers Headbanger’s Ball and Alternative Nation), and NewsBreaks were brought to you by Kurt Loder. This was the heyday of grunge music, and the epicenter of it all was in Seattle, WA.

The musicians of the era had a way of expressing themselves through music that meant something to me, as if certain songs were written with me specifically in mind. Everyone else I know who loves this music feels similarly.

So when I had the chance to go to Seattle for the 2022 AAJ Summer Convention, I wanted to explore a little deeper into the grunge scene, or what was left of it. A daily hive website suggested the following places:

Central Saloon, 207 1st Ave S, Seattle, WA 98104;

Re-bar, 1114 Howell St, Seattle, WA 98101;

Viretta Park, E. John Street at 39th Avenue E, Seattle, WA;

Marco Polo Motel, 4114 Aurora Ave N, Seattle, WA 98103;

El Corazon, 109 Eastlake Ave E, Seattle, WA 98109;

London Bridge Studio, 20021 Ballinger Way NE suite a, Shoreline, WA 98155;

Linda’s Tavern, 707 E Pine St, Seattle, WA 98122; and

The Museum of Pop Culture, 325 5th Ave N, Seattle, WA 98109.

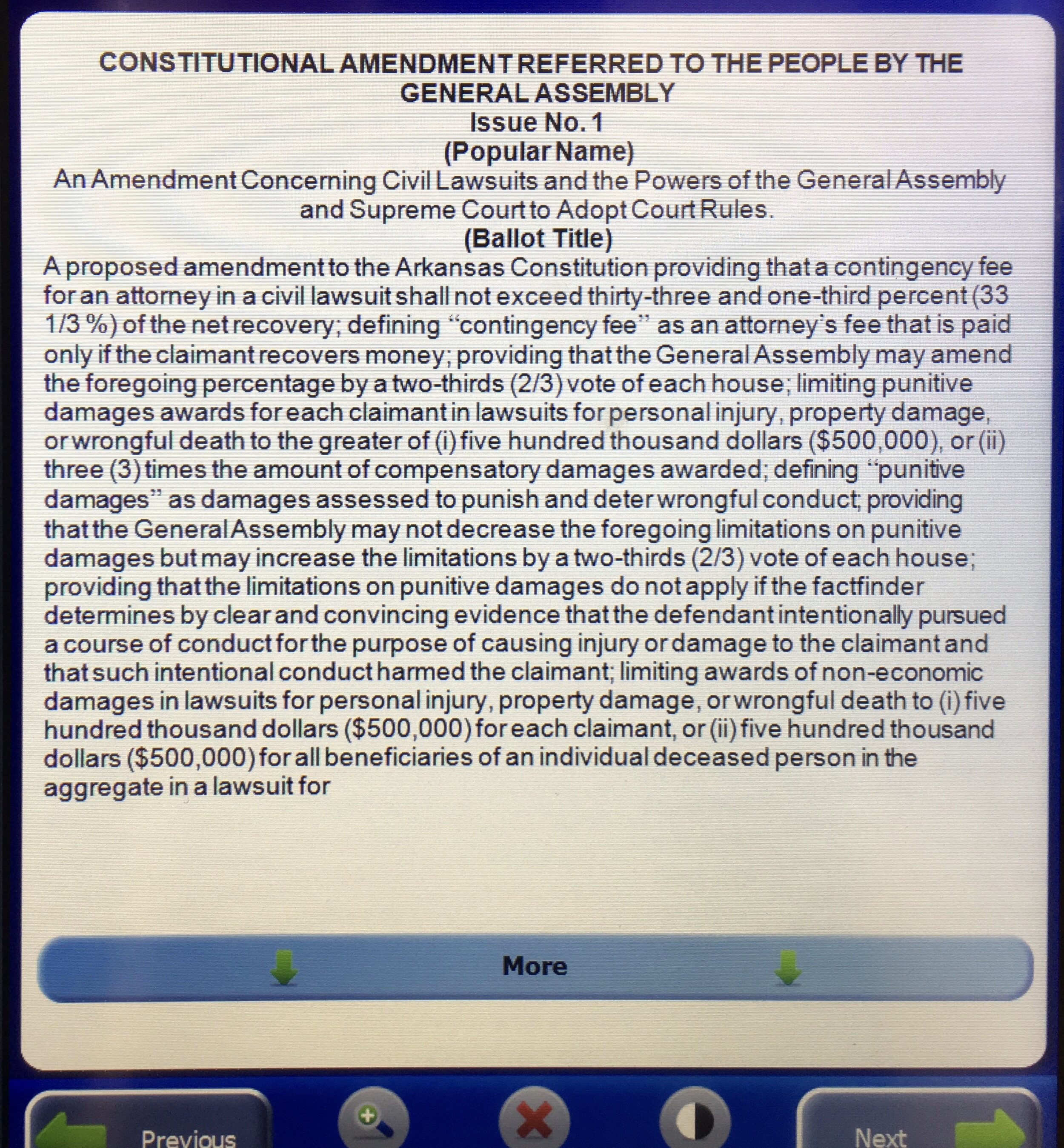

Two fellas from Alabama took the pilgrimage with me. We had no idea what to expect. Our first stop was Viretta Park, which is an unofficial Kurt Cobain memorial. What we didn’t know, was that Cobain lived next door and wrote several songs on the benches in the park, seen below:

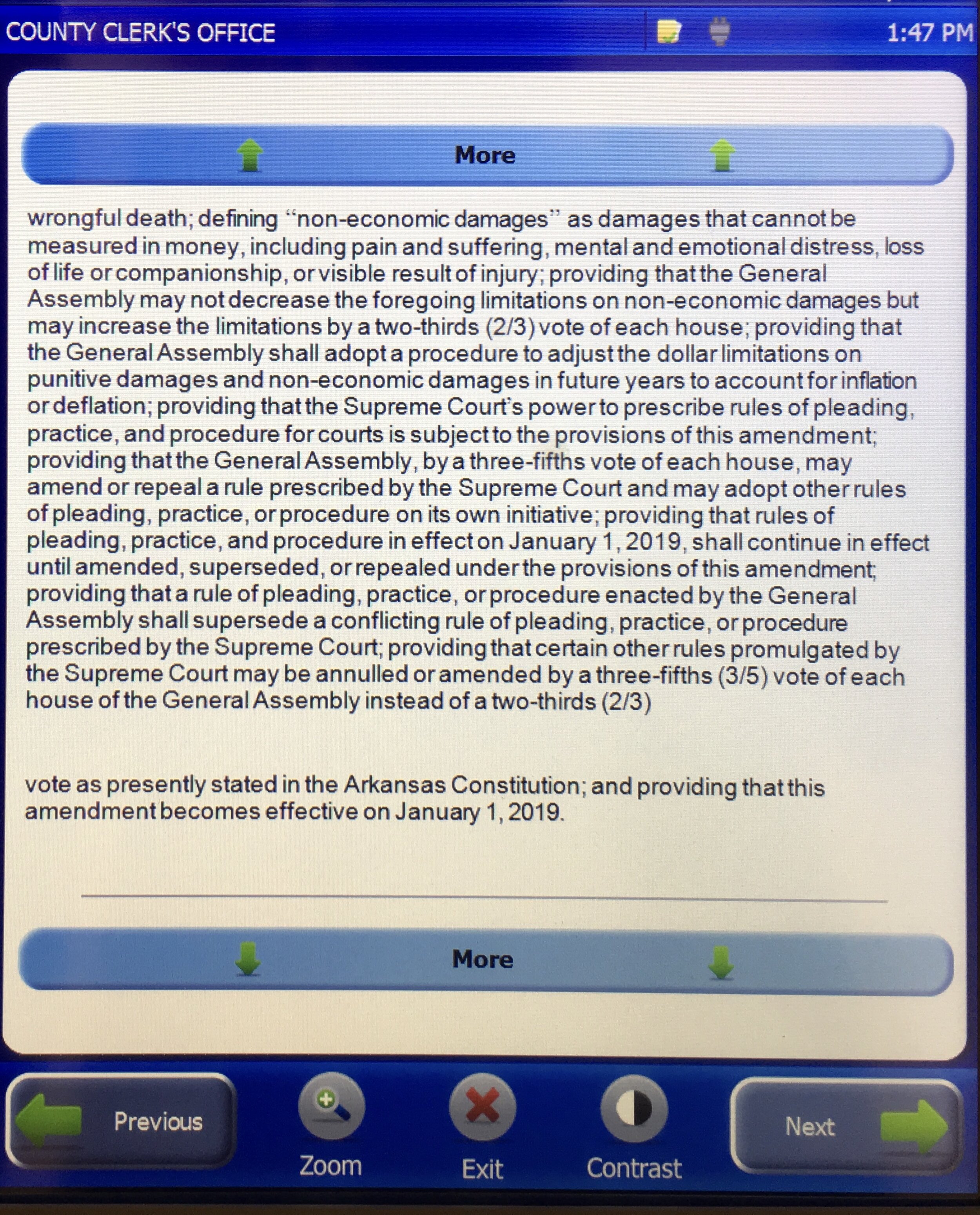

This is one of the Alabama fellas who made the pilgrimage with me.

Another similar bench was dedicated to Layne Staley, the Alice in Chains frontman who passed on April 5, 2002:

Our next stop was London Bridge Studio. When we got there, the outside looked like a bleak industrial building, and was closed. So word to the wise: don’t go on your grunge pilgrimage on a Sunday. We later found out the studio gives tours for $60.00, but we didn’t have time to make it back. The significance of the studio is the many albums it recorded there, including:

Andrew Wood was the frontman for Mother Love Bone. When he passed on March 19, 1990, the Temple of the Dog album noted above was recorded as a tribute to Wood. The remaining members of Mother Love Bone formed “Mookie Blaylock,” which later became known as “Pearl Jam.” El Corazon was where Mookie Blaylock first performed, but it is not there anymore.

Re-bar is where Nirvana got kicked out of their own watch party when Nevermind was released. I went to the address but never found it.

Soundgarden and Alice in Chains were frequently in the rotation at Central Saloon, which is also where Sub Pop Records allegedly first heard and signed Nirvana. I was not able to make it over there.

The Marco Polo Hotel is one of the last places Cobain was seen alive. So was Linda’s Tavern. I did not make it to the hotel, but did get a chance to go to Linda’s Tavern. It was my kind of hole-in-the-wall, with low ceilings and an outside back porch.

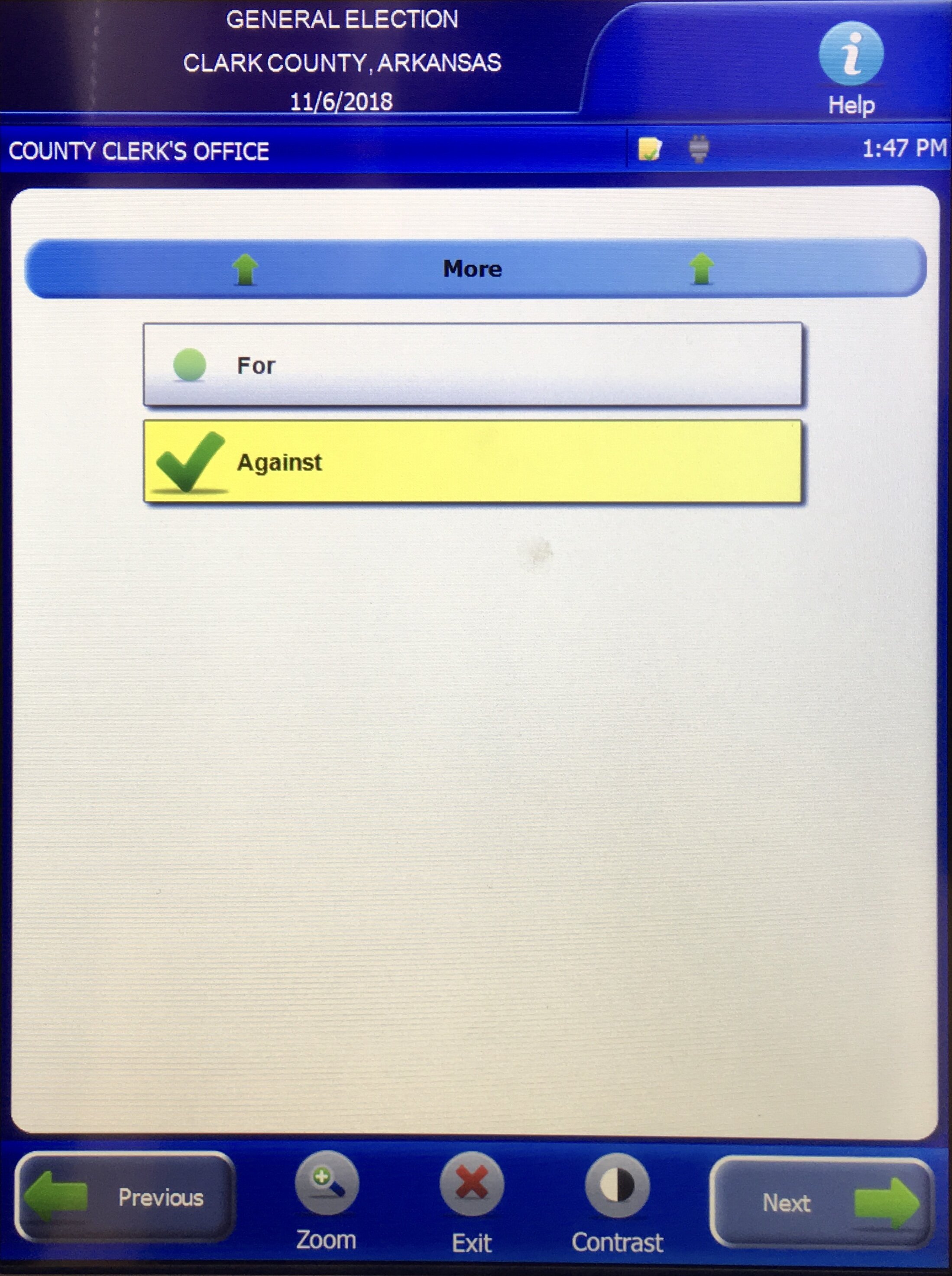

The conference had an event at the Museum of Pop Culture, which was the final stop on the pilgrimage. At the time the article was written in February of 2021, a Pearl Jam exhibit was displayed. That night, the museum featured Jimi Hendrix and Nirvana.

Both exhibits were must sees; simply incredible.

I thought about this post a lot on the way home. I kept coming back to one conclusion. These individuals and bands personified in their music what it means to be misunderstood, giving an outlet to millions who feel the same way, which I suppose we all do at some point. That kind of connection is timeless.