Public Protection Law

/At the Chaney Law Firm, we believe in public protection law. What on earth is public protection law, you ask? It’s a process in which all of us are involved in some form or fahsion, most of us in the form of jury service.

I recently tried a case where I thought the Judge had an excellent explanation to the jury of their role. He explained in no other branch of government, except the judicial branch, does the average person play a role outside of election day. He explained we elect legislators to act on our behalf in the legislative branch to make policy. But, the Judge explained, if you express your concerns to your legislator, the legislator does not necessarily have to listen, or do anything you ask. The same holds true for our elected executives. The Judge explained it is only in the judicial branch, where the average person has the ability to sit on a jury, that regular everyday people can decide what conduct is acceptable, and have their voice heard loud and clear.

Public protection law involves public safety, changing reckless and purposeful misconduct, providing access to justice, and maintaining the independence of the judicial branch of government.

PUBLIC SAFETY

Our society operates smoothly because we share a common set of rules everyone follows so all of us are safe. For example:

We have a right to trust other drivers to follow traffic safety rules so people aren’t hurt in motor vehicle collisions.

We have a right to trust trucking companies will do their due diligence when hiring drivers, and properly train and supervise them.

We have a right to trust doctors will follow the safety rules when performing medical procedures.

We have a right to trust attorneys to follow safety rules so we are informed of our options that will better help us decide our legal matters.

We have a right to trust manufacturers will spend a little more money to make their products safe rather than put their profits over us.

We have a right to trust insurance carriers will follow good-faith claim handling rules to ensure policyholders are adequately protected.

We have a right to trust businesses and other landowners will build and keep their premises safe for their customers.

When someone is harmed because these safety rules aren’t followed, the wrongdoer commits a “tort,” which is a civil wrong. The purpose of tort law is to make an injury victim whole, and to deter wrongdoers from similar conduct. [1] There are typically four things that must be shown in court to hold these wrongdoers accountable. These include whether the safety rule applied to the wrongdoer, whether the wrongdoer violated the safety rule, and whether the safety rule violation caused harm. These three concepts are known as “liability.” [2] The last thing that typically must be shown is amount of the harm.

One aspect of public protection law is about enforcing safety rules to prevent future harm. A rule violator who does not cause harm, like running a stop sign with no other people around, while punishable by criminal law, cannot be held civilly responsible since there is no harm involved. In this respect, the Arkansas Supreme Court has stated as follows:

“Actionable negligence itself is a relational concept. There is no such thing as ‘negligence in the air.’ Conduct without relation to others cannot be negligent; it becomes negligent only as it gives rise to an appreciable risk of injury to others. Acts done in a vacant field or by a lone traveler on a highway may not be negligent; the same acts done in a crowded city or in heavy highway traffic may well be negligent. The concept of actionable negligence is relational because an act is never negligent except in reference to, or toward, some person or legally protected interest.”

The risks from the wrongdoer’s action defines how careful they should be in doing the action; so when the wrongdoer’s conduct creates a more dangerous situation toward other people, they must be more careful to prevent harm. [3] Since the purpose of safety rules is to protect us all from harm, the injured party must show the wrongdoer’s action created possibilities of danger so many and apparent that the safety rule should have protected the injured party against the wrongdoer’s conduct, even when the harm was unintended. [4]

This is public protection law. Local juries get to decide how much harm could have been caused by safety rule violations as part of the relational evaluation required in every case. This is a decision on the value of our societal rules on a case-by-case basis in which juries use their “common sense, common experience, and [apply] … the standards and behavioral norms of [their] community.” [5] What a country we live in that allows our local communities to decide which societal rules are important to us.

CHANGING PURPOSEFUL AND RECKLESS MISCONDUCT

Public protection law is also about changing purposeful and reckless misconduct for the public good. While the law allows juries to return verdicts to make injury victims whole, it also allows juries to return verdicts for the purpose of punishing and deterring wrongdoers from reckless or purposeful misconduct. [6] These type of verdicts are known as “punitive damages,” which are allowed since big businesses and corporations cannot be put in jail.

In this respect, the Arkansas Supreme Court acknowledged simply making a policyholder whole from insurance carrier fraud in an occasional lawsuit would not deter the carrier, or others, “from seeking a wrongful gain by similarly victimizing hundreds of other policyholders. Punitive damages will have a deterrent effect in a case of this type.” [7] For example, a punitive damages verdict was upheld where a carrier attempted to shut down a Little Rock physician’s physical therapy practice by decreasing the amount of claims the carrier had to pay. The evidence supporting the verdict included the carrier’s claim practices and use of a computer program, illustrating a program of “economic warfare” against people making claims for connective tissue injuries, part of which included low-ball offers and the threat of protracted litigation to discourage these claims. [8] Putting a stop to such purposeful and reckless misconduct is public protection law.

Likewise, in a case where State Farm refused to settle a claim made against one of its policyholders, a Utah jury returned a $145 million punitive damages verdict, which was upheld on appeal by the Utah Supreme Court in 2001. You can read about the State Farm’s conduct leading up to this verdict here. State Farm appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, and argued the punitive verdict violated State Farm’s 14th Amendment due process rights. The Court agreed and decided punitive verdicts most likely conform to due process when they are single digit multipliers of the verdict to make the injury victim whole. This case changed the way State Farm does business because it now has a company business practice of paying verdicts over its at-fault insureds’ policy limits. Changing such purposeful and reckless misconduct is the purpose of public protection law.

Many politicians, big businesses, as well as the State and National Chamber of Commerce have been trying to impose a cap on punitive damages for years, if not decades. You can read more about this here. The effect of such caps will allow big business and corporations to factor in harming people as a cost of doing business. The threat of punitive damages serves as an incentive for big business and corporations to not harm people in the pursuit of profit. Thus, a purpose of punitive damages is public protection.

There are already rules in place to measure whether punitive damages are too much in any given case, which make caps unnecessary. These rules include the following:

The degree of reprehensibility;

The ratio between the harm or potential harm sustained and the punitive damages verdict; and

The difference between the remedy in factor #2 and comparable civil penalties authorized or imposed in similar cases. [9]

Factor #1 looks at the enormity of the misconduct, as some conduct is more blameworthy than others. Intentional conduct designed to economically harm someone, targeting financially vulnerable people, and whether the wrongdoer is a repeat offender are relevant considerations. [10]

Factor #2 addresses whether there is a reasonable relationship between the amount it took to make the injury victim whole, and the amount of the punitive damages verdict. A relevant consideration is not only the harm that resulted, but also the harm likely to result from the misconduct. Reasonableness is always part of this factor’s decision-making formula. [11]

Factor #3 looks at statutes imposing fines for the misconduct. The purpose of this factor is to determine whether less drastic remedies are available to deter the misconduct in question. [12]

These three factors are considered by courts to protect wrongdoers from excessive punitive verdicts. A cap on punitive verdicts is a form of corporate welfare having the effect of giving businesses the ability to pencil in how much it will cost them for intentionally hurting people.

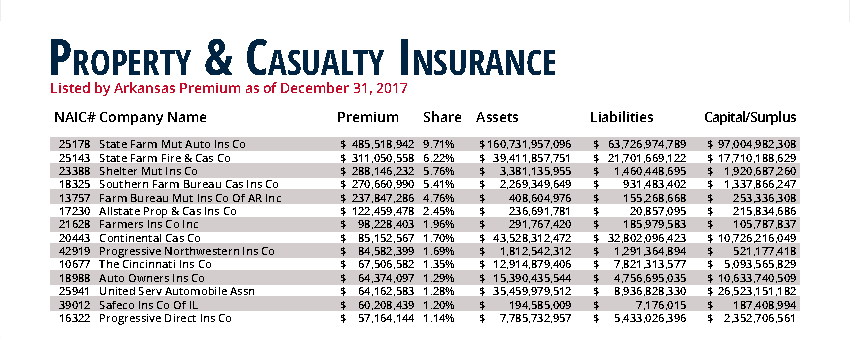

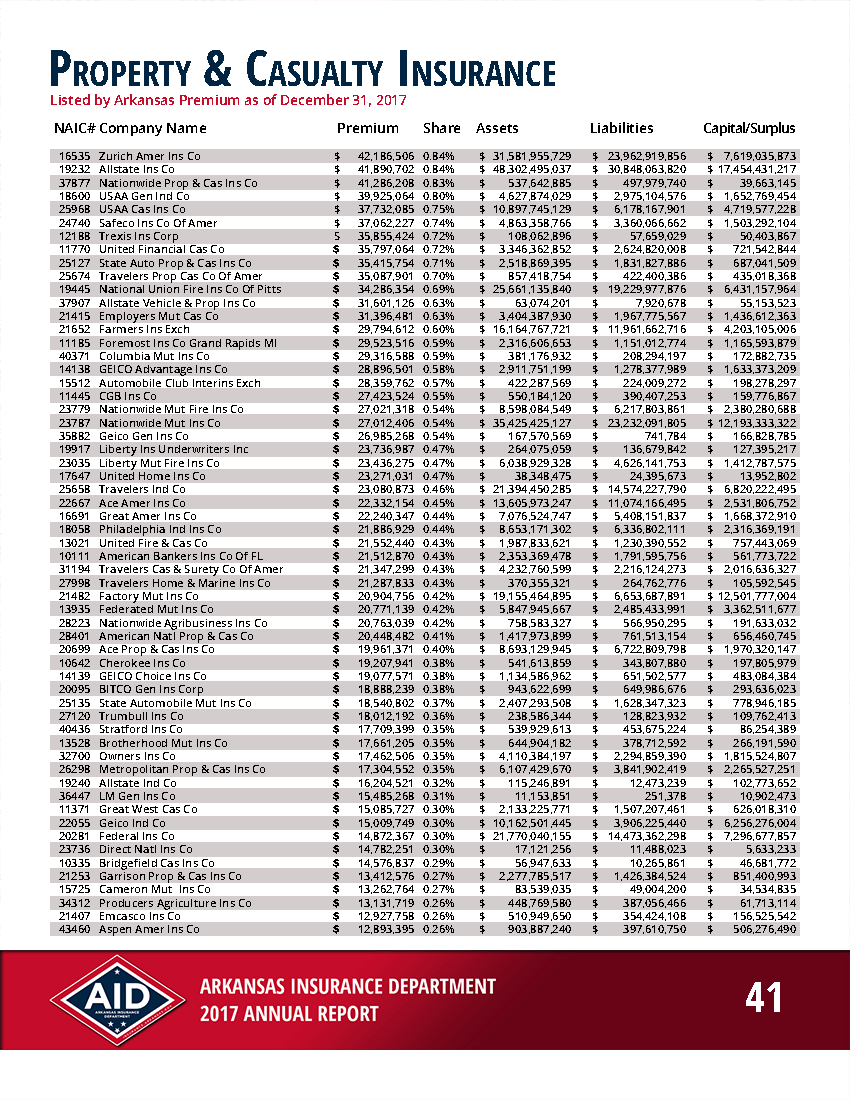

Consider the following the example, which is an excerpt from the Arkansas Insurance Department’s 2017 Annual Report for property and casualty insurance:

Topping the list with a nearly 10% market share, the report indicates State Farm’s property and casualty insurance company made over $485 million dollars in premiums in Arkansas for 2017. Do you really think a punitive cap of $1 or $5 million dollars, which represents 0.20% and 1.03% of State Farm’s annual revenue in 2017, is going to deter them from doing business as usual? While $1 or $5 million dollars may be a lot of money to you and me, it is a slap on the wrist for a company making $485 million dollars per year in the state of Arkansas alone. The same analogy holds true with any company.

In addition to the above, any type of one-size-fits-all damages cap restricts the local control juries have to decide what conduct is acceptable within their own communities. Since all cases are different, imposing a cap takes away a jury’s right to determine the facts of the case before it. A damages cap is another way of bureaucrats, who will never hear the facts of an individual case, telling you facts don’t matter, and your jury service doesn’t matter. This undermines the ability of regular everyday people to protect themselves from purposeful and reckless misconduct, and significantly weakens public protection law.

ACCESS TO JUSTICE

In 2003, the Arkansas Bar Association petitioned the Arkansas Supreme Court to form the Arkansas Access to Justice Commission. Since then, the Commission has undertaken initiatives about the following topics:

Expanding pro bono recruitment and participation;

Implementing court assistance projects;

Effecting changes to statutes and court rules that impact access to justice;

Educating the public about the need for civil legal aid; and

Increasing financial resources available to provide legal assistance to low-income Arkansans.

One of the changes to court rules impacting access to justice was a change to the Arkansas Rules of Professional Conduct, which allows attorneys to provide short-term legal services without an expectation of continued representation. The purpose of the rule change was to permit attorneys to represent under served communities with their legal issues and give them access to justice. [13] Improved access to justice is public protection law.

One of the ways people have access to justice is through the method by which attorneys are paid. In tort cases, attorneys are paid through a contingency fee, which provides access to justice to regular everyday people who otherwise would not be able to afford an attorney who charges by the hour. The way it works is fees and expenses come out of a percentage of a clients’ total recovery, if any. So attorneys working on a contingency fee rise and fall together with their clients.

The contingency fee keeps the courthouse doors open for people hurt through no fault of their own by safety rule-violating wrongdoers, because it allows everyday hard-working people to stand toe-to-toe with multi billion dollar corporations in a courtroom. Thus, limiting contingency fees limits access to justice, and limits public protection law. If you believe the attorney you’re talking to is charging too much, we encourage you to shop around. This is a better option than imposing a one-size fits all rule limiting the contingency fee for all attorneys, since it would also limit access to justice, the communities’ ability to seek redress for wrongs, and public protection law.

INDEPENDENCE OF THE JUDICIARY

According to the framers of the Constitution, judicial independence from the other branches of government was a critical part of the separation of powers. One federal judge described judicial independence in this way:

“The Framers were particularly concerned about guarding against a too powerful Legislative branch, not an overreaching Executive. They also wanted to ensure that the rights of the minority were protected against a tyranny of the majority. Their answer was to provide for an independent federal judiciary that would keep the other two branches in check. The Framers believed an independent judiciary was central to a republican form of government and critical to fairness and impartiality.”

In this manner, an independent judiciary is by definition public protection. These concepts were described in an article in the American Bar Association Journal a few years back, as follows:

“Characteristic of an independent and strong judiciary is that its courts are free of and unfettered by politics and political interference, and its decisions are based on legal merits rather than what is popular or politically expedient. Indeed, when to do so is consistent with the rule of law, courts must resist and withstand the pressures of political and public opinion in order to remain fair and impartial.”

The most extreme example I can think of where a court was subject to the pressures of political and public opinion was in Nazi Germany. In 1934, Hitler decreed only members of the Nazis party could be judges. Do you really think these judges were impartial?

The above picture is meant to be Roland Freisler, and if you were before him, you had a 90% chance of being sentenced to life in prison or death. Wikipedia uses Freisler’s court as the definition of a “Kangaroo Court.” While the example is extreme, it makes the point of why judicial independence is so important in a free society.

Judicial Independence Under Attack in Arkansas

In 2000, Arkansas voters approved Amendment 80 to the Arkansas Constitution, which confirmed our judicial branch’s authority to make rules of “pleading, practice, and procedure.” All this means is our Supreme Court is in control of regulating the procedural rules of our court system, including the rules of evidence, professional conduct, civil procedure, etc. These procedural rules are not matters of public policy; our elected state senators and representatives are in charge of making public policy by enacting laws.

In 2003, the Arkansas General Assembly passed Act 649, which was known as the Civil Justice Reform Act (“CJRA”). The Arkansas Supreme Court struck down many provisions of the Act because it sought to enact procedural rules, rather than public policy. [14] The Court held other parts of the CJRA were unconstitutional because it violated the Arkansas Constitution’s prohibition on damages caps to persons or property. [15]

These holdings prompted the State Chamber of Commerce, the nursing home industry, and other big business leaders to take away Amendment 80’s rule-making authority from our Supreme Court. In the 89th General Assembly in 2013-14, the joint subcommittee responsible for referring out constitutional amendments voted against referring an amendment that would have put a price on life, and taken rule-making control away from our Supreme Court.

Undeterred, the same interest groups gathered signatures in a ballot initiative with the same goal after the 90th General Assembly in 2015-16. This proposed amendment, known as “Issue No. 4,” would have imposed an arbitrary cap of $250,000 on “non-economic” damages in medical injury lawsuits (including suits against nursing homes), imposed a cap on the contingency fees attorneys could charge, and taken away the Arkansas Supreme Court’s exclusive ability to make procedural rules governing our court system. In a challenge to the sufficiency of the ballot title, the Arkansas Supreme Court held a critical term in the ballot title, “non-economic damages,” was left undefined. Accordingly, the Court ordered the Secretary of State from counting or certifying votes for the proposed amendment.

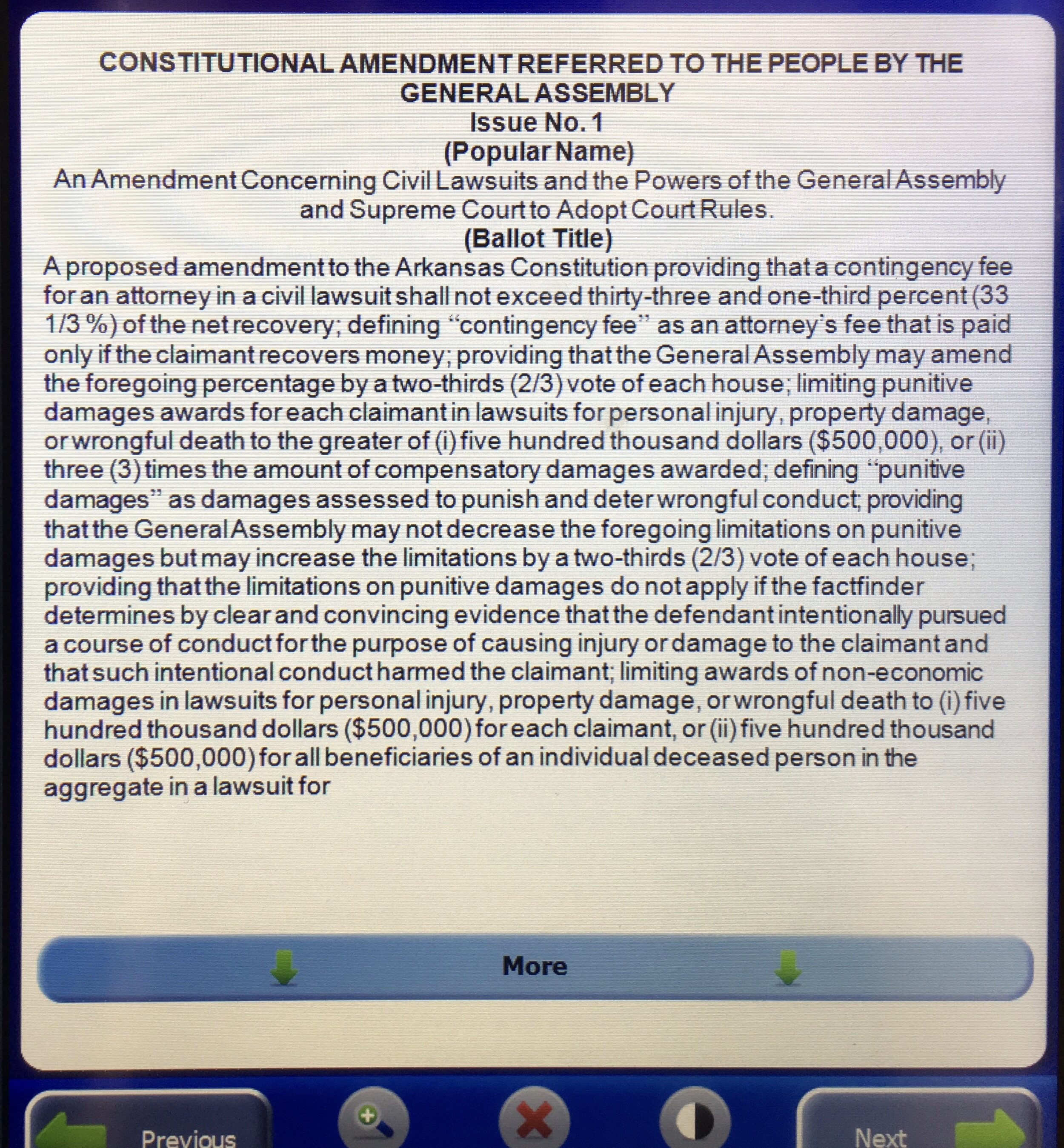

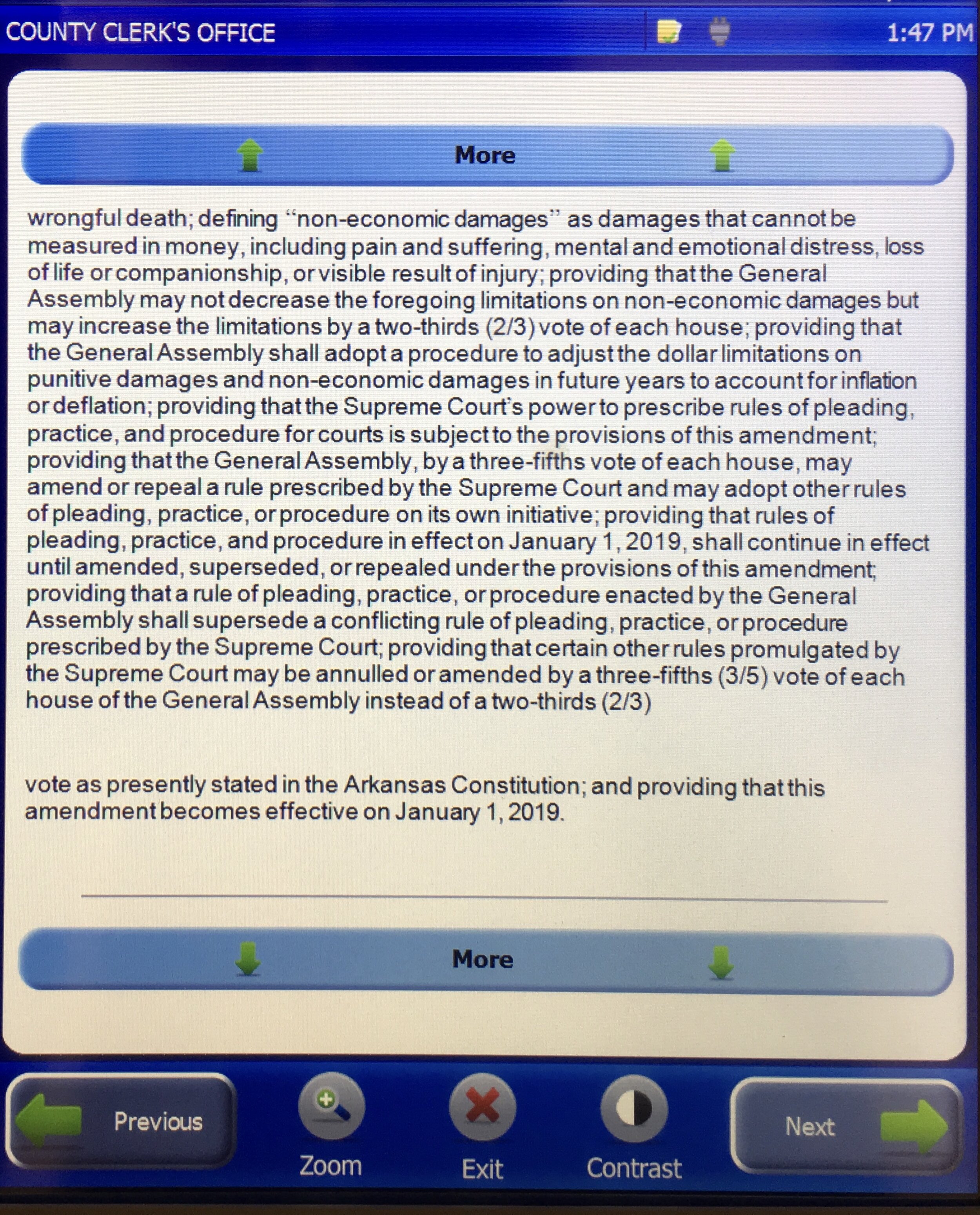

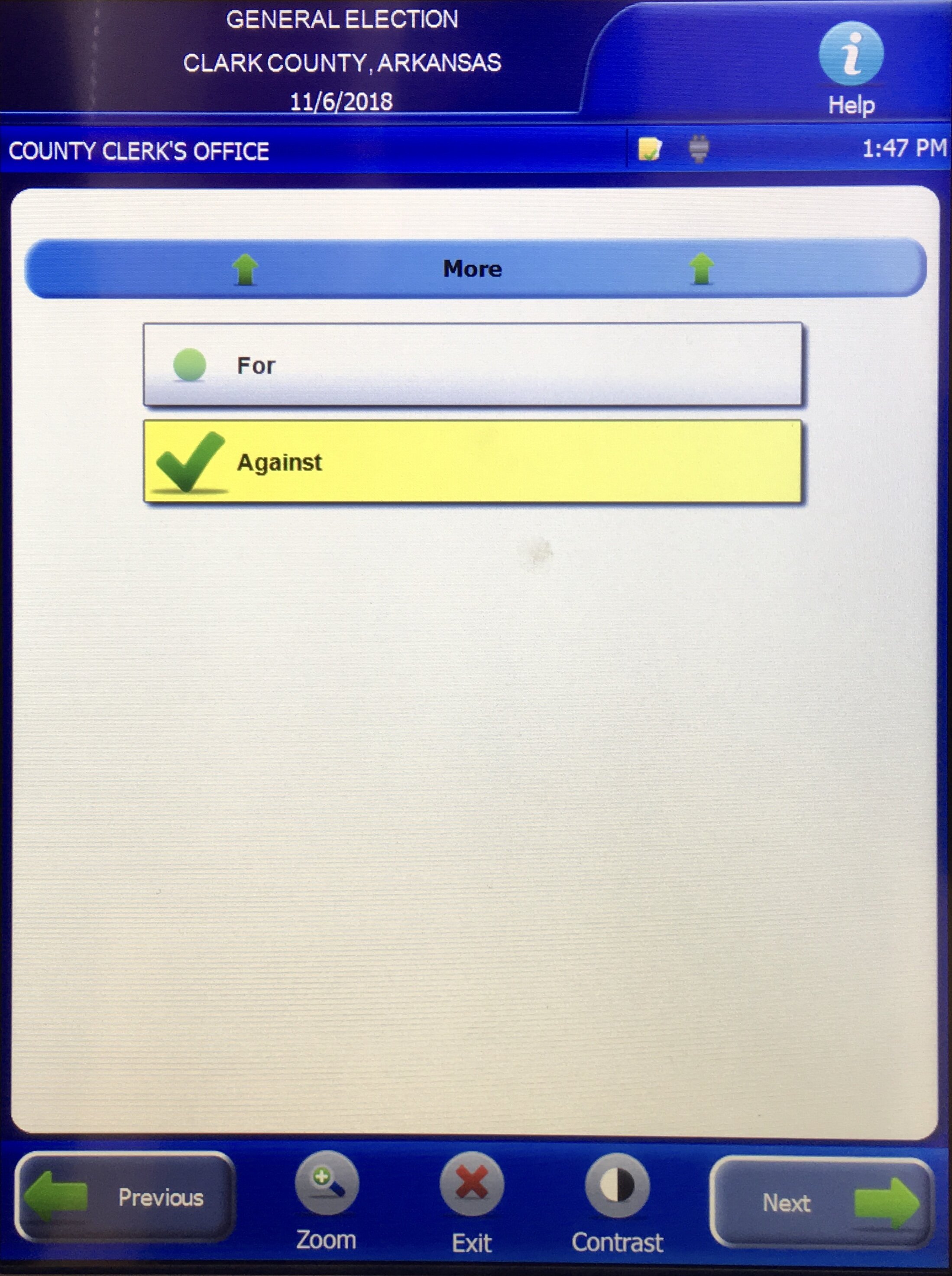

In the 91st General Assembly in 2017-18, legislators referred a more aggressive constitutional amendment to the voters. This time, the amendment would have changed the Arkansas Constitution in the following ways:

A cap of $500,000 for non-economic damages in any lawsuit resulting in injury or death. "Non-economic" damages were defined as "damages that cannot be measured in money, including without limitation any loss or damage, however characterized, for pain and suffering, mental and emotional distress, loss of life or companionship, or the visible result of injury;

A cap of $500,000 for punitive damages unless the facts showed a wrongdoer intentionally pursued a course of conduct causing injury or damage, and the intentional conduct caused damage to an injury victim;

Give the General Assembly the authority to enact laws amending, repealing, or adopting on its own initiative rules of pleading, practice, or procedure, which supersede such rules adopted by the Arkansas Supreme Court. This section explicitly stated these rules include the presentation and admission of evidence; and

A cap of 33 1/3% for contingency fees of an injury victim's attorney of the net amount recovered, regardless of how the recovery is obtained.

A legal challenge to the amendment was ultimately successful. The Arkansas Supreme Court held the amendment violated the requirement in Article 19 § 22 of the Arkansas Constitution that referred constitutional amendments be single subjects so voters don’t have to choose between parts of an amendment they like, and parts they don’t.

All of these amendments, if passed, would have significantly weakened public protection from corporate wrongdoing, put a price on life, restricted access to justice, and taken away the independence of our judiciary. It reminds me of the following quote:

“Those who would give up essential Liberty, to purchase a little temporary Safety, deserve neither Liberty nor Safety.”

Weakening public protection law accomplishes exactly what Benjamin Franklin was trying to say. Public protection law is the core of our civil justice system, and is designed to hold wrongdoers accountable for their actions. Weakening the civil justice system in the guise of “safety,” takes away both liberty and safety, regardless of how it is accomplished, whether it be through damages caps (which limit people’s ability to decide what conduct is acceptable within their communities), limiting access to justice, or taking away the independence of the judiciary. This is because when big businesses can harm people as a line-item cost of doing business, none of us are safe from their conduct. Examples abound, and here is a great one. [16]

Regular everyday Arkansas people have plenty of common sense to decide our civil disputes. Based on the information before them, they know when something is right or wrong, and act accordingly. The public is only protected where the public has a say in the type of protection it desires. There is no need to overhaul the entire system, limit access to justice, jeopardize the independence of our judiciary, and limit the role average people play in our government by having big brother unilaterally decide what conduct is acceptable within our own communities.

[1] See City of Monterey v. Del Monte Dunes, 526 U.S. 687, 727, 119 S. Ct. 1624, 1647, 143 L. Ed. 2d 882, 917 (1999) (Scalia, J., concurring); Minneci v. Pollard, 565 U.S. 118, 127, 132 S. Ct. 617, 624, 181 L. Ed. 2d 606, 614 (2012).

[2] See e.g., Jones v. McGraw, 374 Ark. 483, 486, 288 S.W.3d 623, 626 (2008).

[3] Palsgraf v. Long Island R. Co., 248 N.Y. 339, 344, 162 N.E. 99 (1928).

[4] Cobb v. Indian Springs, Inc., 258 Ark. 9, 23, 522 S.W.2d 383, 390 (1975) (Fogelman, J., concurring) (quoting Palsgraf, 248 N.Y. at 345, 162 N.E. at 101).

[6] Bayer CropScience LP v. Shafer, 2011 Ark. 518 at 12-13, 385 S.W.3d 822, 831.

[7] Empl. Equit. Life Ins. Co. v. Williams, 282 Ark. 29, 30, 665 S.W.2d 873, 874 (1984).

[8] Allstate Ins. Co. v. Dodson, 2011 Ark. 19 at 21, 376 S.W.3d 414, 428.

[9] BMW of N. Am. v. Gore, 517 U.S. 559, 575, 116 S. Ct. 1589, 1598-99 134 L. Ed. 2d 809, 826 (1996).

[10] Id. at 575-80, 116 S. Ct. at 1599-1601, 134 L. Ed. 2d at 826-829.

[11] Id. at 580-83, 116 S. Ct. at 1601-03, 134 L. Ed. 2d at 829-31.

[12] Id. at 583-85, 116 S. Ct. at 1603-04, 134 L. Ed. 2d at 831-32.

[13] Ark. R. Prof. Conduct 6.5.

[14] Johnson v. Rockwell Automation, Inc., 2009 Ark. 241 at 8-10, 308 S.W.3d 135, 141-42 (holding non-party fault and medical cost provisions of the CJRA unconstitutional because these provisions were procedural, but upholding the CJRA’s end to joint-and-several liability).

[15] Bayer CropScience LP v. Shafer, 2011 Ark. 518 at 13, 385 S.W.3d 822, 831-32 (holding the CJRA’s punitive damages cap unconstitutional in violation of Ark. Const. Art 5 § 32, prohibiting damages caps for injuries to persons or property).

[16] See Schmidt v. Ramsey, 860 F.3d 1038 (8th Cir. 2017) (where a child was born with severe brain damage, the parents of the child brought suit against the doctors and hospital responsible for the child’s injuries, which resulted in a jury returning a verdict in the amount of $17 million dollars based on the needs of the child throughout her life. After the jury verdict, the trial court reduced its amount to $1.75 million according to the Nebraska Hospital Medical Liability Act (“the Act”), and the parents appealed the decision to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 8th Circuit. The Court upheld the reduction, reasoning that 1) the hospital did not have to post an opt-out notice to patients who may fall under the Act; 2) the Act’s cap on damages did not violate the 7th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution because the Act did not determine damages in the first instance, it just imposed an upper limit on the determination; 3) the Act did not deprive the child of a vested property interest under the 5th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution; 4) the child failed to show medical malpractice victims will have difficulty in obtaining access to justice because of the Act; 5) the Act had a rational basis when passed and does not violate equal protection even though it treats catastrophically injured people differently than those without such injuries; and 6) the Act did not violate principles of substantive due process). For more information, see Hot Coffee, a documentary that came out in 2010 about these and other similar topics.