Impact of attorneys in the Civil Rights Movement

/As we turn the page into February, I am reminded about the contributions attorneys made in the Civil Rights Movement. These efforts defined the contours of our modern constitutional law, explained below.

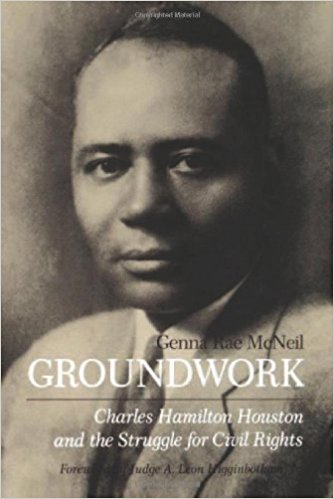

Charles Hamilton Houston is credited by the NAACP with the idea that "unequal education is the Achilles heel of Jim Crow." After graduating from Harvard Law School in 1923, Mr. Houston was admitted to the District of Columbia Bar and began practicing law with his father in 1924.

After serving in World War I, Mr. Houston entered Harvard Law School in the fall of 1919. He became the first African American to serve as editor of the Harvard Law Review in 1922.

From 1929 to 1935, he served as Vice-Dean and Dean of the Howard University School of Law. He influenced nearly 25% of all of the African American attorneys in the United States at the time.

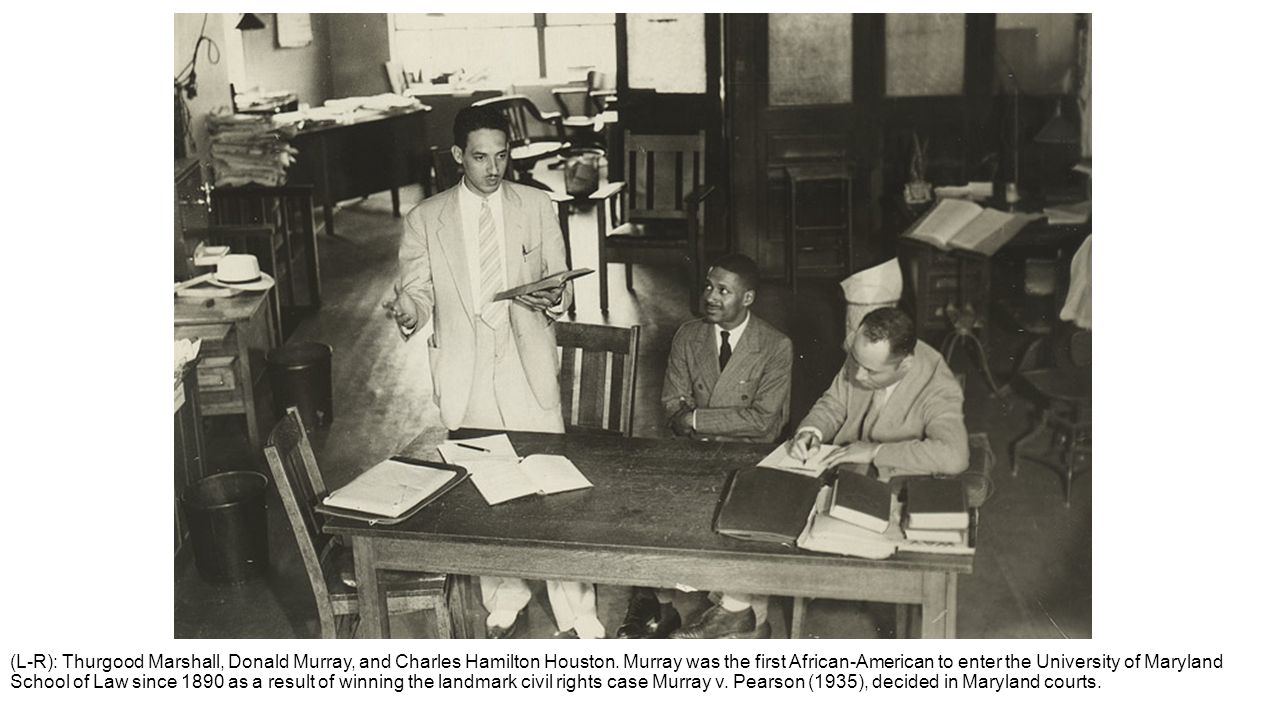

Mr. Houston fought for equal education specifically as a mechanism to fight segregation generally. One of Mr. Houston's pupils at Howard was Thurgood Marshall, who graduated from Howard University's School of Law in 1933.

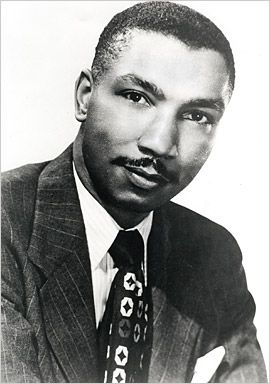

Thurgood Marshall at age 28.

With his mentor, Mr. Houston, Mr. Marshall co-represented Donald Gaines Murray, who sought admission to the University of Maryland's School of Law. The school denied the young 22-year old African American Amherst College graduate admission to the law school solely because of his race. See Pearson v. Murray, 169 Md. 478, 182 A. 590 (1936).

Mr. Marshall argued the law school's exclusion of Murray violated state law, as well as the 14th Amendment to the United States Constitution. The trial court agreed with Mr. Marshall, and ordered the law school to admit Murray. The school filed an appeal to the Maryland Court of Appeals. However, the Court of Appeals upheld the trial court's order for the school to admit Murray. They reasoned the school was a branch or agency of state government, and thereby came "under the constitutional mandates applicable to the actions of states." Id. at 483, 182 A. at 592. The Court acknowledged the state could legally provide separate locations for law schools for each race provided that citizens of each race were educated upon equal terms. Id. at 485, 182 A. 592-93. However, because the state did not provide a separate law school for African Americans, the Court held this violated Murray's right to equal protection of the laws under the 14th Amendment. Id. at 487, 182 A. 593-94.

After the legal victory in Pearson v. Murray, supra, Mr. Houston sought to extend the precedent set by the case to the entire country in Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U.S. 337, 59 S. Ct. 232, 83 L. Ed. 208 (1938) ("Gaines"). As in Pearson, Mr. Houston argued the 14th Amendment prohibited the State of Missouri from not allowing his client, Lloyd Gaines, to attend the state's all-white law school because the state did not provide a law school for African Americans to attend. The state argued Gaines could attend law schools in adjacent states. In adopting the reasoning from Pearson, supra, the United States Supreme Court stated as follows;

The admissibility of laws separating the races in the enjoyment of privileges afforded by the State rests wholly upon the equality of the privileges which the laws give to the separated groups within the State. The question here is not of a duty of the State to supply legal training, or of the quality of the training which it does supply, but of its duty when it provides such training to furnish it to the residents of the State upon the basis of an equality of right. By the operation of the laws of Missouri a privilege has been created for white law students which is denied to negroes by reason of their race. The white resident is afforded legal education within the State; the negro resident having the same qualifications is refused it there and must go outside the State to obtain it. That is a denial of the equality of legal right to the enjoyment of the privilege which the State has set up, and the provision for the payment of tuition fees in another State does not remove the discrimination.

Gaines, 305 U.S. at 349-50, 59 S. Ct. at 236, 83 L. Ed. at 213. The U.S. Supreme Court would later follow this case in Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 U.S. 631, 68 S. Ct. 299, 92 L. Ed. 247 (1948), whereby Gaines' counterpart in Oklahoma (also represented Mr. Marshall) sought admission to the University of Oklahoma School of Law, but was denied for the same reason.

While Gaines was essential to the legal strategy to defeat segregation, his life ended in obscurity when he vanished in 1939 in Chicago, IL at the age of 28 never to be seen or heard from again. The University of Missouri School of Law has an outstanding digital collection of resources that sheds light on the economic difficulties that Gaines and his family faced in working to provide him with an advanced education.

In 1940, Mr. Marshall founded the NAACP Legal Defense Fund ("LDF"), which is the country's first and foremost civil and human rights law firm. Mr. Marshall talked about his early NAACP legal work here.

Mr. Marshall would hire and work with several attorneys who made significant contributions to the LDF and the Civil Rights Movement in general, including William Henry Hastie (who was one of Mr. Marshall's professors at Howard, worked on many cases with Mr. Marshall and Mr. Houston, helped integrate the military, and was the first African American federal judge when he was appointed to the federal district court in the Virgin Islands in 1937; he would later be nominated by President Harry Truman to the Third Circuit Court of Appeals in 1950 where he would serve until 1971); Jack Greenberg (who served as director counsel after Mr. Marshall until 1984); Constance Baker Motley (who became the first African American woman elected to the New York state senate in 1964, and the first African American woman to be appointed as a federal judge in 1966 when she joined the federal bench in the Southern District of New York); Spottswood W. Robinson III (who became the legal representative of the LDF in Virginia in 1948, and later became dean at Howard's law school from 1960-63, and was named a U.S. District Judge for the District of Columbia from 1964-66 before being the first African American appointed to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia where he retired in 1989); Louis L. Redding (the only African American attorney in Delaware for two decades was prominent in fighting for integration as the LDF's representative in that state); William Robert Ming, Jr. (who was part of the litigation team for nearly every case mentioned herein, and successfully obtained an acquittal in May of 1960 of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. from a Montgomery, Alabama jury on perjury charges related to tax evasion); Frank D. Reeves (who worked at the LDF fighting for desegregation, later became a law professor at Howard during the 1960s, and was one of those who seconded John F. Kennedy's nomination for president in 1960); Andrew D. Weinberger (who helped develop several of the cases mentioned herein, including Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1, 87 S. Ct. 1817, 18 L. Ed. 2d 1010 (1967) (holding miscegenation laws violated the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution)); and Michael Meltsner (who was the second white attorney on the LDF staff, and filed hundreds of lawsuits in the 1960s to integrate major southern institutions, and would later become a law professor at Columbia, Northeastern where he became dean, and Harvard).

On June 18, 1940, Mr. Marshall and his law school classmate, Oliver Hill, received a favorable decision by the 4th Circuit Court of Appeals. The Court held the school board of Norfolk, Virginia could not pay a lower rate to an equally qualified African American teacher than to a white teacher without violating the due process and equal protection clauses of the 14th Amendment. Alston v. School Bd., 112 F.2d 992 (4th Cir. 1940). Citing Gibson v. Mississippi, 162 U.S. 565, 16 S. Ct. 904, 40 L. Ed. 1075 (1896), the Court reasoned as follows:

Underlying all of those decisions is the principle that the constitution of the United States, in its present form, forbids, so far as civil and political rights are concerned, discrimination by the general government, or by the states, against any citizen because of his race. All citizens are equal before the law. The guaranties of life, liberty, and property are for all persons, within the jurisdiction of the United States, or of any state, without discrimination against any because of their race. Those guaranties, when their violation is properly presented in the regular course of proceedings, must be enforced in the courts, both of the nation and of the state, without reference to considerations based upon race.

Mr. Marshall represented and won more cases (14-19) before the U.S. Supreme Court than any other American. These cases include, but are not limited to Chambers v. Florida, 309 U.S. 227, 60 S. Ct. 472, 84 L. Ed. 716 (1940) (holding compulsory confessions by law enforcement officers violated the due process rights of four indigent African American defendants who were sentenced to death); Smith v. Alllwright, 321 U.S. 649, 64 S. Ct. 757, 88 L. Ed. 987 (1944) (holding political parties cannot deny citizens the opportunity to vote by casting its electoral process in a form permitting a private organization to practice racial discrimination in an election); Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U.S. 373, 66 S. Ct. 1050, 90 L. Ed. 1317 (1946) (holding a Virginia statute unconstitutional that sought to segregate people of different races during interstate travel); Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1, 21-22, 68 S. Ct. , 92 L. Ed. 1161, 1184-85 (1948) (holding the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment prohibits states from judicially enforcing restrictive covenants on real estate based on race); Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629, 70 S. Ct. 848, 94 L. Ed. 1114 (1950) (holding the University of Texas Law School's refusal to admit an African American as a student violated the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment, but failed to reexamine the "separate but equal" doctrine established in Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537, 16 S. Ct. 1138, 41 L. Ed. 256 (1896)); and McLaurin v. Okla. State Regents for Higher Educ., 339 U.S. 637, 70 S. Ct. 851, 94 L. Ed. 1149 (1950) (same as Sweatt, supra).

Graduating just behind Mr. Marshall from Howard was Mr. Hill (center). His case, Davis v. County School Board, 103 F. Supp. 337 (E.D. Va. 1952), was one of the consolidated cases in the Brown decision. The encyclopedia of Virginia has an excellent entry here on Mr. Hill's work and life.

Perhaps Mr. Marshall's crowning achievement as a private attorney was co-representing children (with some of the other attorneys pictured above and local counsel) from Kansas, South Carolina, Virginia, and Delaware who sought to attend public schools in their respective states, but were denied on the basis of race.

In Brown v. Bd. of Educ., 347 U.S. 483, 495, 74 S. Ct. 686, 692, 98 L. Ed. 873, 881 (1954), the U.S. Supreme Court finally held [s]eparate educational facilities are inherently unequal," and deprived Mr. Marshall's clients equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the 14th Amendment.

From right to left, George E.C. Hayes, Mr. Marshall, and James M. Nabrit III after the Brown decision was announced. Mr. Hayes' companion case to Brown (both decided on May 17, 1954), Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497, 74 S. Ct. 693, 98 L. Ed. 884 (1954), held segregation in public schools in the District of Columbia was a denial of due process of law under the 5th Amendment.

Mr. Nabrit was one of Mr. Marshall's many pupils. He joined the LDF in 1959. His appellate advocacy work helped transform American society in several aspects (education, access to public accommodations, and free speech).

The Brown decision would serve as a legal building block of the Civil Rights Movement. Mr. Marshall worked closely with Robert Lee Carter on that case and many others. Mr. Carter began working for Mr. Marshall in 1944 after serving in World War II. In 1956, Mr. Carter succeeded Mr. Marshall as general counsel for the NAACP.

Mr. Carter graduated from Lincoln University and Howard Law School, and earned a Master of Law degree from Columbia University. He helped prepare briefs in the McLaurin and Sweatt cases cited above, and argued McLaurin before the Oklahoma Supreme Court and the U.S. Supreme Court. Mr. Carter was a key aide in the Brown case. He recommended using social science research to prove the negative effects of racial segregation, which became a crucial factor in the Brown decision. He also wrote the brief for the Brown case and delivered the argument before the U.S. Supreme Court. He served as the NAACP’s General Counsel for 12 years to 1968. In 1972 President Nixon appointed Carter to the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York, where he presided until his death on January 3, 2012. The Library of Congress has a three hour oral history interview with Mr. Carter here.

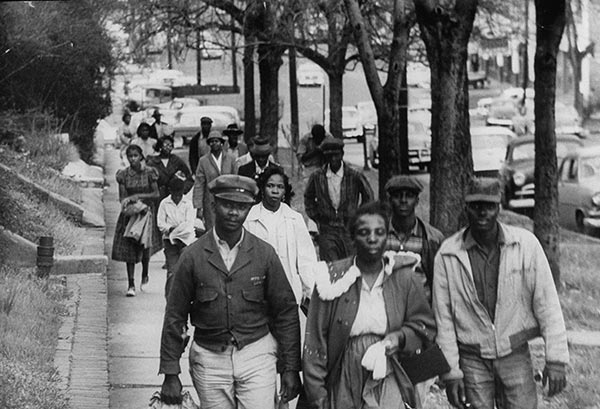

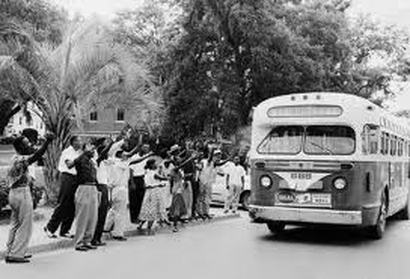

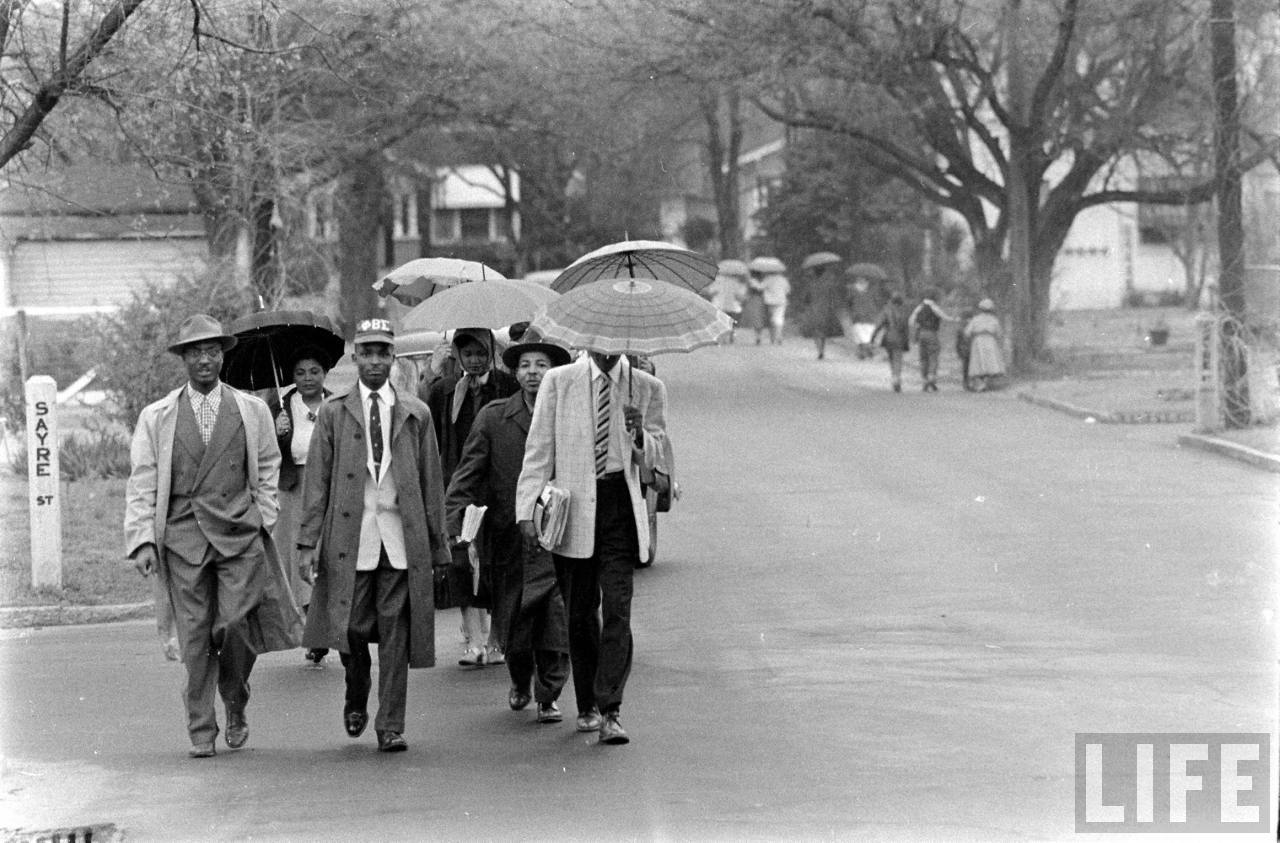

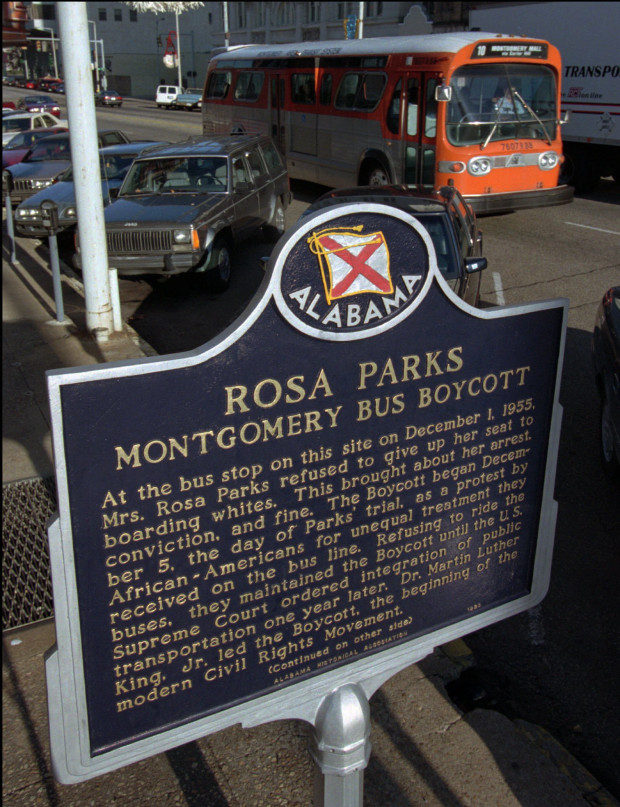

The year before Mr. Carter took over as general counsel for the NAACP, Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat to a white person on a public transportation bus in Montgomery, Alabama in defiance of the state's segregation laws. The events that followed are detailed in a movie called Boycott.

The movie tells the story of the Montgomery bus boycotts at the beginning of the Civil Rights Movement. From my limited perspective, I thought the movie did a good job of illustrating the challenges faced by the African American citizens who boycotted.

At one point, the movie shows the apprehension of the boycotters of being arrested. To alleviate their fears, Fred David Gray (played by Sean Michael Howard), as the attorney for the Montgomery Improvement Association and its members who organized the boycott, tells the boycotting citizens they will be bailed out of jail.

What ended up happening was much more than just being bailed out of jail. Mr. Gray (and others) challenged segregation laws as being unconstitutional. This resulted in a series of landmark United States Supreme Court opinions.

The movie briefly mentions the legal challenge to the segregation laws that led to the bus boycott. Mr. Gray (and others) filed suit on behalf of four African American citizens and others similarly situated in Browder v. Gayle, 142 F. Supp. 707 (M.D. Ala. 1956) against several Montgomery city officials, the company who owned the buses, and two of its drivers. Mr. Gray argued enforcement of "separate but equal" laws violated several provisions of the 14th Amendment, and sought an injunction prohibiting city officials from enforcing Alabama's segregation laws. A three judge panel found as follows:

We cannot in good conscience perform our duty as judges by blindly following the precedent of Plessy v. Ferguson, [163 U.S. 537, 16 S. Ct. 1138, 41 L. Ed. 256 (1896)] when our study leaves us in complete agreement … that the separate but equal doctrine can no longer be safely followed as a correct statement of the law. In fact, we think that Plessy v. Ferguson has been impliedly, though not explicitly, overruled, and that, under the later decisions, there is now no rational basis upon which the separate but equal doctrine can be validly applied to public carrier transportation within the City of Montgomery and its police jurisdiction. The application of that doctrine cannot be justified as a proper execution of the state police power.

We hold that the statutes and ordinances requiring segregation of the white and colored races on the motor buses of a common carrier of passengers in the City of Montgomery and its police jurisdiction violate the due process and equal protection of the law clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.

Browder, 142 F. Supp. at 717. The United States Supreme Court affirmed the decision on November 13, 1956. Gayle v. Browder, 352 U.S. 903, 77 S. Ct. 145, 1 L. Ed. 2d 114 (1956) (citing Brown, 347 U.S. 483, 74 S. Ct. 686, 98 L. Ed. 873; Baltimore City v. Dawson, 350 U.S. 877, 76 S. Ct. 133, 100 L. Ed. 774 (1955); and Holmes v. Atlanta, 350 U.S. 879, 76 S. Ct. 141, 100 L. Ed. 776 (1955)).

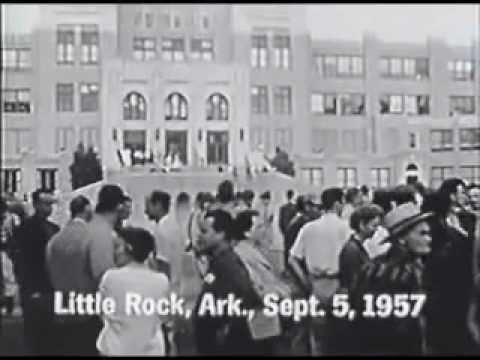

During the same time period, Arkansas' own Wiley A. Branton, Sr. (who had previously encouraged Silas Hunt to apply to the University of Arkansas School of Law), together with Mr. Marshall and others, represented African American children seeking to integrate the Little Rock School District. See Aaron v. Cooper, 143 F. Supp. 855 (E.D. Ark. 1956). On behalf of his clients, Mr. Branton sought to enforce the mandate by the U.S. Supreme Court in Brown, 347 U.S. 483, 74 S. Ct. 686, 98 L. Ed. 873 against the Little Rock School Board and its superintendent. However, on August 27, 1956, the judge for the federal District Court for the Eastern District of Arkansas stated he would not "substitute its own judgment for that of the [school authorities]" in implementing an integration plan. Aaron, 143 F. Supp. at 866.

Mr. Branton would appeal to the 8th Circuit Court of Appeals, but in the intervening year the events of the Little Rock desegregation crises occurred.

The Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals agreed with Mr. Branton on August 18, 1958, by stating as follows:

An impossible situation could well develop if the District Court's order were affirmed. Every school district in which integration is publicly opposed by overt acts would have 'justifiable excuse' to petition the courts for delay and suspension in integration programs. An affirmance of 'temporary delay' in Little Rock would amount to an open invitation to elements in other districts to overtly act out public opposition through violent and unlawful means. The Supreme Court of the United States has specifically determined that segregation in the public schools is a deprivation of the equal protection of laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment.

. . .

The issue plainly comes down to the question of whether overt public resistance, including mob protest, constitutes sufficient cause to nullify an order of the federal court directing the Board to proceed with its integration plan. We say the time has not yet come in these United States when an order of a Federal Court must be whittled away, watered down, or shamefully withdrawn in the face of violent and unlawful acts of individual citizens in opposition thereto.

Aaron v. Cooper, 257 F.2d 33, 40 (8th Cir. 1958). The Little Rock School Board and its superintendent appealed to the United States Supreme Court. See Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1, 78 S. Ct. 1401, 3 L. Ed. 2d 5 (1958).

Daisy Bates (center) posing in front of the U.S. Supreme Court building with six of the nine African American students who integrated Little Rock (Central) High School. Represented by Mr. Carter and Pine Bluff, Arkansas native George Howard, Jr., Bates would later successfully challenge Little Rock and North Little Rock ordinances that demanded city officials be provided with a list of names of the members of the local branch of the NAACP. The U.S. Supreme Court held the ordinances unconstitutionally infringed on the freedom of association. See Bates v. City of Little Rock, 361 U.S. 516, 80 S. Ct. 412, 4 L. Ed. 2d 480 (1960).

On September 12, 1958, the U.S. Supreme Court issued its opinion, which strongly disagreed with the school authorities by stating the case:

necessarily involve[d] a claim by the Governor and Legislature of a State that there is no duty on state officials to obey federal court orders resting on this Court's considered interpretation of the United States Constitution. Specifically it involves actions by the Governor and Legislature of Arkansas upon the premise that they are not bound by our holding in Brown, 347 U.S. 483, 74 S. Ct. 686, 98 L. Ed. 873.

Cooper, 358 U.S. at 4, 78 S. Ct. at 1402, 3 L. Ed. 2d at 8. The Court held "the federal judiciary is supreme in the exposition of the law of the Constitution ... [which is] a permanent and indispensable feature of our constitutional system." Thus, the Court's interpretation of the 14th Amendment in the Brown opinion was the supreme law of the land. The Court further stated:

No state legislator or executive or judicial officer can war against the Constitution without violating his undertaking to support it. ... If the legislatures of the several states may, at will, annul the judgments of the courts of the United States, and destroy the rights acquired under those judgments, the constitution itself becomes a solemn mockery. A Governor who asserts a power to nullify a federal court order is similarly restrained. If he had such power, … it is manifest that the fiat of a state Governor, and not the Constitution of the United States, would be the supreme law of the land; that the restrictions of the Federal Constitution upon the exercise of state power would be but impotent phrases.

It is, of course, quite true that the responsibility for public education is primarily the concern of the States, but it is equally true that such responsibilities, like all other state activity, must be exercised consistently with federal constitutional requirements as they apply to state action.

Cooper, 358 U.S. at 18, 78 S. Ct. at 1410, 3 L. Ed. 2d at 17. While the school authorities argued integration would cause violence, the Court concluded preservation of public peace cannot be accomplished by laws or ordinances that deny rights created or protected by the Federal Constitution. Cooper, 358 U.S. at 16, 78 S. Ct. at 1409, 3 L. Ed. 2d at 16. The Court held school children have a constitutional right to be free from racial discrimination in school admission, which can neither be nullified openly and directly by [any public servant in any branch of government], "nor nullified indirectly by them through evasive schemes for segregation whether attempted 'ingeniously or ingenuously.'" Id. at 17, 78 S. Ct. at 1409, 3 L. Ed. 2d at 16.

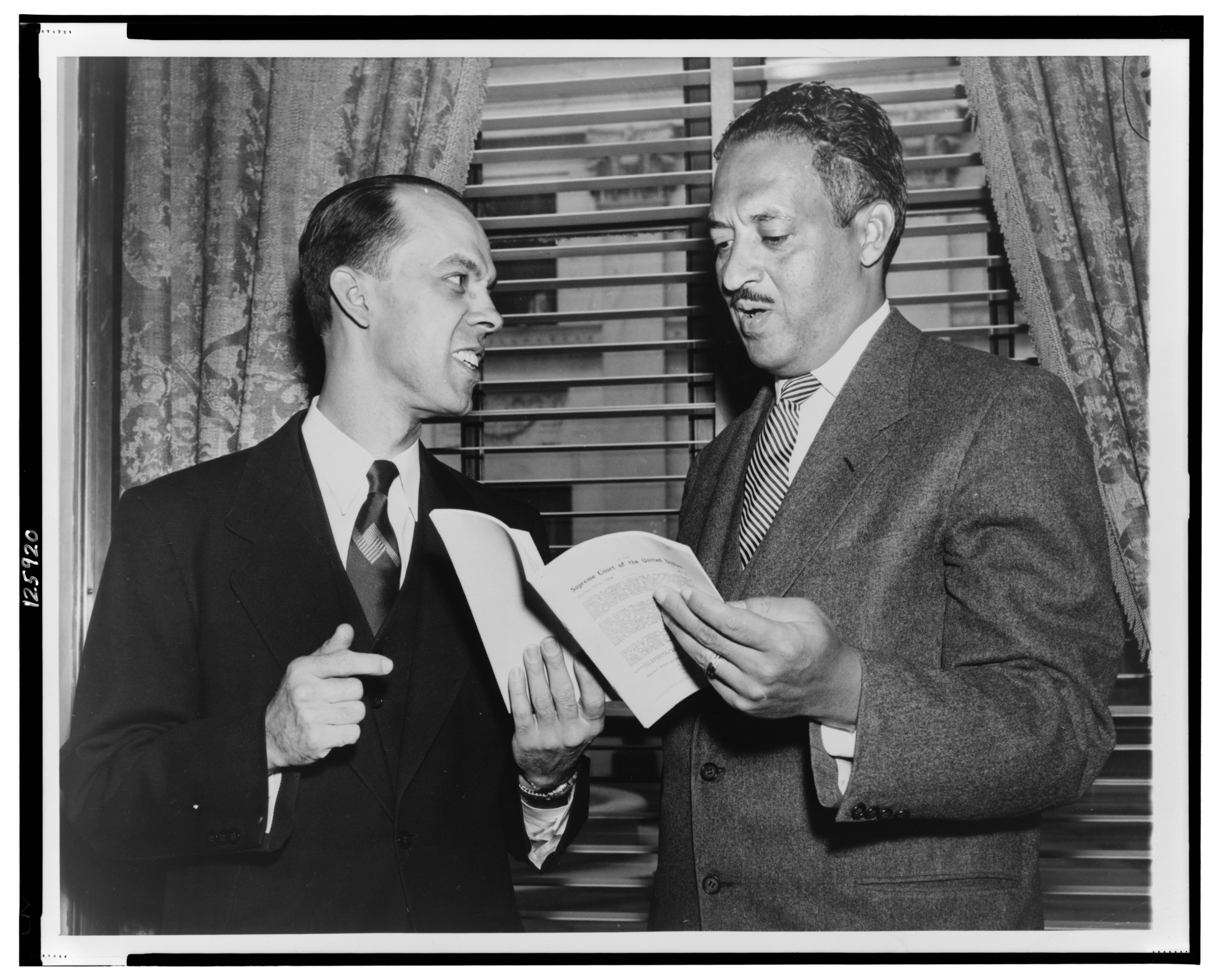

Wiley Branton, Sr. (left) and Thurgood Marshall (right) at a court hearing about the desegregation of Little Rock's public schools. Mr. Marshall would ultimately become the first African American and the 96th Justice on the United States Supreme Court on June 13, 1967 after being nominated by President Lyndon Johnson to replace Tom C. Clark.

The Encyclopedia of Arkansas has an excellent entry about Mr. Branton. His son is currently the Circuit Judge of Pulaski County's Eighth Division.

Four months before Cooper came down from the U.S. Supreme Court, Mr. Branton received another favorable decision by the same Court. Mr. Branton took the case of a 19-year old African American man from Jefferson County, Arkansas with a 5th grade education who was convicted of first degree murder and sentenced to death. See Payne v. Arkansas, 356 U.S. 560, 78 S. Ct. 844, 2 L. Ed. 2d 975 (1958). Because the young defendant was threatened with mob violence by a jailer if he did not confess, Mr. Branton sought to exclude the confession. The trial court refused to do so, and the young defendant was convicted by a jury. The U.S. Supreme Court held this was a deprivation of "that fundamental fairness essential to the very concept of justice, and hence, denied [the young defendant] due process of law, guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment." Id. at 567, 78 S. Ct. at 850, 2 L. Ed. 2d at 981.

After the Montgomery bus boycotts in 1955 and the litigation that followed, Mr. Gray participated in several other important civil rights cases. One case was Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339, 81 S. Ct. 125, 5 L. Ed. 2d 110 (1960), where Mr. Gray and Mr. Carter represented African American citizens of Tuskegee, Alabama who opposed an Alabama gerrymandering statute that would have allowed the municipal government of Tuskegee to alter the shape of the city from a square figure to a 28-sided figure, as seen below.

Arguing on behalf of the Tuskegee residents, Mr. Gray argued this constituted a discrimination against them in violation of the due process and equal protection clauses of the 14th Amendment, and denied them the right to vote in defiance of the 15th Amendment of the United States Constitution. In response, the city argued the residents failed to state a claim upon which relief could be granted. The federal District Court for the Middle District of Alabama agreed with the city, as did the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals.

However, the United States Supreme Court reversed. The Court reasoned as follows:

It is inconceivable that guaranties embedded in the Constitution of the United States may ... be manipulated out of existence [by cloaking legislation that impaired the right to vote in the garb of the realignment of political subdivisions].

. . .

[States] are not insulated from federal judicial review ... when state power is used as an instrument for circumventing a federally protected right. This principle has had many applications. It has long been recognized in cases which have prohibited a State from exploiting a power acknowledged to be absolute in an isolated context to justify the imposition of an unconstitutional condition. What the Court has said in those cases is equally applicable here, ... that Acts [passed by a state legislature that are] generally lawful may become unlawful when done to accomplish an unlawful end, and a constitutional power cannot be used by way of condition to attain an unconstitutional result. The [Tuskegee citizens] are entitled to prove their allegations at trial.

Gomillion, 364 U.S. at 345-48, 81 S. Ct. at 129-30, 5 L. Ed. 2d at 115-17.

In another of Mr. Gray's cases, the Attorney General for Alabama obtained an ex parte restraining order in 1956 barring the NAACP from conducting any business within the state. The NAACP, represented by Mr. Gray and Mr. Carter, sought to enjoin enforcement of the order. See NAACP v. Alabama, 377 U.S. 288, 84 S. Ct. 1302, 12 L. Ed. 2d 325 (1964). The case went up to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1958, 1959, and 1961. Five years after the restraining order was issued, a state court found the NAACP had violated the order and other state laws, which was upheld by the Alabama Supreme Court, because they found one assignment of error without merit, and refused to consider the remaining assignments of error.

Autherine Lucy (left) with Thurgood Marshall (center) and Birmingham attorney Arthur Shores. After the Montgomery bus boycotts and Lucy being the first African American admitted to the University of Alabama, the Alabama Attorney General attempted to oust the NAACP from the state in part because it allegedly did not comply with state law for out of state corporations.

On June 1, 1964, the United States Supreme Court held "[n]ovelty in procedural requirements cannot be permitted to thwart review in this Court applied for by those who, in justified reliance upon prior decisions, seek vindication in state courts of their federal constitutional rights." Id. at 301, 84 S. Ct. at 1311, 12 L. Ed. 2d at 335. The Court proceeded to the merits of the case, and decided it by stating as follows:

It is beyond debate that freedom to engage in association for the advancement of beliefs and ideas is an inseparable aspect of the 'liberty' assured by the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, which embraces freedom of speech.

This Court has repeatedly held that a governmental purpose to control or prevent activities constitutionally subject to state regulation may not be achieved by means which sweep unnecessarily broadly and thereby invade the area of protected freedoms. The power to regulate must be so exercised as not, in attaining a permissible end, unduly to infringe the protected freedom. Even though the governmental purpose be legitimate and substantial, that purpose cannot be pursued by means that broadly stifle fundamental personal liberties when the end can be more narrowly achieved. ... This principle is applicable here even though the ouster of the petitioner from Alabama has been accomplished solely by judicial act; whether legislative or judicial, it is still the application of state power which we are asked to scrutinize.

In the first proceedings in this case, we held that the compelled disclosure of the names of the petitioner's members would entail the likelihood of a substantial restraint upon the exercise by petitioner's members of their right to freedom of association. It is obvious that the complete suppression of the Association's activities in Alabama which was accomplished by the order below is an even more serious abridgment of that right. The allegations of illegal conduct contained in the third charge against the petitioner suggest no legitimate governmental objective which requires such restraint.

. . .

This case, in truth, involves not the privilege of a corporation to do business in a State, but rather the freedom of individuals to associate for the collective advocacy of ideas. Freedoms such as this are protected not only against heavyhanded frontal attack, but also from being stifled by more subtle governmental interference.

Id. at 307-10, 84 S. Ct. at 1314-15, 12 L. Ed. 2d at 338-40 (citations omitted).

Mr. Howard would continue fighting for the freedom of association by challenging an Arkansas law requiring teachers at state supported schools as a precondition to employment to disclose every organization to which they belonged without limitation within the preceding five years.

In addition to fighting for the freedom of association, Mr. Howard was part of the legal team that desegregated high schools in Fort Smith, Arkansas {see Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198, 86 S. Ct. 348, 15 L. Ed. 2d 265 (1965)) and many other locations across the state. Mr. Howard was appointed by Governor Winthrop Rockefeller to the Arkansas State Claims Commission in 1969. Mr. Howard would later serve on the Arkansas Supreme Court and on the Arkansas Court of Appeals. President Jimmy Carter appointed him as District Court Judge for the Eastern District of Arkansas in 1980. The federal building in Pine Bluff was named for Mr. Howard shortly after his death on April 21, 2007.

While the Arkansas Supreme Court upheld the validity of the law, the United States Supreme Court reversed. Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U.S. 479, 81 S. Ct. 247, 5 L. Ed. 2d 231 (1960). The Court stated there was a relevant governmental interest asserted into the fitness and competence of teachers, which distinguished NAACP v. Alabama, supra and Bates, supra. However, the Court reasoned as follows:

It is not disputed that to compel a teacher to disclose his every associational tie is to impair that teacher's right of free association, a right closely allied to freedom of speech and a right which, like free speech, lies at the foundation of a free society. Such interference with personal freedom is conspicuously accented when the teacher serves at the absolute will of those to whom the disclosure must be made -- those who any year can terminate the teacher's employment without bringing charges, without notice, without a hearing, without affording an opportunity to explain.

The statute does not provide that the information it requires be kept confidential. Each school board is left free to deal with the information as it wishes. The record contains evidence to indicate that fear of public disclosure is neither theoretical nor groundless. Even if there were no disclosure to the general public, the pressure upon a teacher to avoid any ties which might displease those who control his professional destiny would be constant and heavy. Public exposure, bringing with it the possibility of public pressures upon school boards to discharge teachers who belong to unpopular or minority organizations, would simply operate to widen and aggravate the impairment of constitutional liberty.

The vigilant protection of constitutional freedoms is nowhere more vital than in the community of American schools. By limiting the power of the States to interfere with freedom of speech and freedom of inquiry and freedom of association, the Fourteenth Amendment protects all persons, no matter what their calling. But, in view of the nature of the teacher's relation to the effective exercise of the rights which are safeguarded by the Bill of Rights and by the Fourteenth Amendment, inhibition of freedom of thought, and of action upon thought, in the case of teachers brings the safeguards of those amendments vividly into operation. Such unwarranted inhibition upon the free spirit of teachers has an unmistakable tendency to chill that free play of the spirit which all teachers ought especially to cultivate and practice; it makes for caution and timidity in their associations by potential teachers. Scholarship cannot flourish in an atmosphere of suspicion and distrust. Teachers and students must always remain free to inquire, to study and to evaluate.

Id. at 485-87, 81 S. Ct. at 251, 5 L. Ed. 2d at 236-37 (citations omitted).

In another significant event in the Civil Rights Movement, James Meredith sought to transfer from Jackson State University to the University of Mississippi in 1961. After five months of writing letters to the school, the Ole Miss registrar's office responded to Meredith's application. In denying his application on May 25, 1961, the school stated it would not admit Meredith because Jackson State was not a member of the Southern Association of Colleges and Secondary Schools, Ole Miss did not recognize the programs offered by Jackson State, and Meredith's letters of recommendation were insufficient for "either a resident or nonresident applicant." See Meredith v. Fair, 298 F. 2d 696, 698-99 (5th Cir. 1962). Meredith filed suit in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Mississippi four days later.

Seen above are Meredith (left), and his attorneys Constance Baker Motley (center) and R. Jess Brown (right) on June 1, 1961. Mr. Brown filed some of the first Civil Rights lawsuits in Mississippi in the late 1940s and 1950s. In addition to Meredith, Mr. Brown worked with the LDF fighting discrimination in transportation and other public accommodations in 1960s.

The Court denied Meredith's motion for a preliminary injunction that would have enjoined Ole Miss from denying Meredith admission to the school based on his race. Meredith appealed to the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals. The Court took "judicial notice that the state of Mississippi maintain[ed] a policy of segregation in its schools [and] colleges" in defiance of the Brown decision. Id. at 701. The Court found the school's requirement for letters of recommendation from Ole Miss alumni was a denial of equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment because traditional social barriers made it unlikely, if not impossible, for African Americans to get such recommendations. Id. at 702. The Court noted Meredith did not get a fair trial from the District Court, and ordered the District Court to have a trial on the merits to determine whether Ole Miss' decision was based on non-discriminatory grounds. Id. at 702-03.

Pictured above is Meredith (left) with Medgar Evers (right). Evers was the first state field secretary of the NAACP in Mississippi, and helped Meredith through the process of getting enrolled at Ole Miss. Evers was assassinated outside of his home in Jackson, MS on June 12, 1963.

The second trial produced the same result. The District Court judge denied Meredith the relief he requested and dismissed his Complaint. Again, Meredith appealed. See Meredith v. Fair, 305 F.2d 343 (5th Cir. 1962). The Court went through the facts of the entire case, and drew the inference that the delay in trying the case was "designed to defeat [Meredith] by discouragingly high obstacles that would result in the case carrying through his senior year." Id. at 352. The Court found the recommendation requirement and Ole Miss' transfer policy was applied in a discriminatory manner to Meredith based on the evidence. The Court concluded as follows:

Reading the 1350 pages in the record as a whole, we find that James Meredith's application for transfer to the University of Mississippi was turned down solely because he was a Negro. We see no valid, non-discriminatory reason for the University's not accepting Meredith. Instead, we see a well-defined pattern of delays and frustrations, part of a Fabian policy of worrying the enemy into defeat while time worked for the defenders.

Id. at 361.

On September 25, 1962, Meredith was prohibited from enrolling at Ole Miss despite the federal court order(s) allowing him to do so. The next day, Meredith was prohibited from entering the Ole Miss campus by the Mississippi Lieutenant Governor, acting on the instructions from the Governor, Ross Barnett. As a result, Barnett was held in civil contempt and ordered to pay $10,000 per day while being held in the custody of the authority of the U.S. Attorney General, Bobby Kennedy. See Meredith v. Fair, 313 F.2d 532 (5th Cir. 1962).

Evers (center) embracing Meredith (left) and iconic writer James Baldwin (right), who covered the Civil Rights Movement for magazines such as The New Yorker. Van Evers is the child in front.

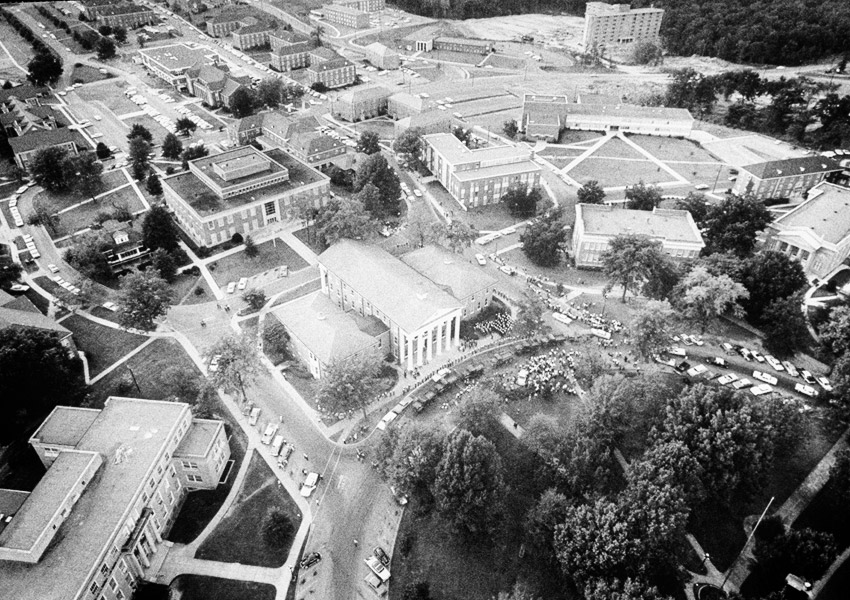

What happened next had been foreshadowed by the events in Little Rock in the fall of 1957 (the similarity even extended to the football teams of Little Rock Central and Ole Miss, who both would perform well on the field in each respective autumn). On September 30, 1962, the Ole Miss campus erupted into a full scale riot in response to Meredith's enrollment, which had to be put down by federal troops. An ESPN Outside the Lines article by Wright Thompson explored these events in detail a few years ago, which is an excellent read.

In 2008, the lyceum at Ole Miss (center) was designated a national historic landmark by the national park service. The commemorating plaque concludes "the riotous event marked a decisive turning point in the history of public school desegregation as violent southern massive resistance declined in the face of federal government enforcement."

With the protection of federal marshals for the next year, Meredith graduated from Ole Miss in August of 1963.

The University of Southern Mississippi's Center for Oral History & Cultural Heritage has an oral history with Meredith's attorney, R. Jess Brown, here. There is pending legislation at the federal level to name the federal courthouse in Jackson after Mr. Brown.

On July 2, 1964, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (42 U.S.C. § 2000) became law, and made discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin illegal. In 2016, a movie named All the Way documented the events in detail that led up to the Act's passage.

President Lyndon Johnson and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. shake hands after Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act into law.

The Civil Rights Act hastened the end of state segregation laws. For example, state laws outlawing persons remaining on the premises of a business after being told to leave were held to be in conflict with the Civil Rights Act. See Hamm v. Rock Hill, 379 U.S. 306, 85 S. Ct. 384, 13 L. Ed. 2d 300 (1964). This opinion consolidated cases from Arkansas and South Carolina whereby the petitioners were African Americans who had engaged in sit-ins after being refused service.

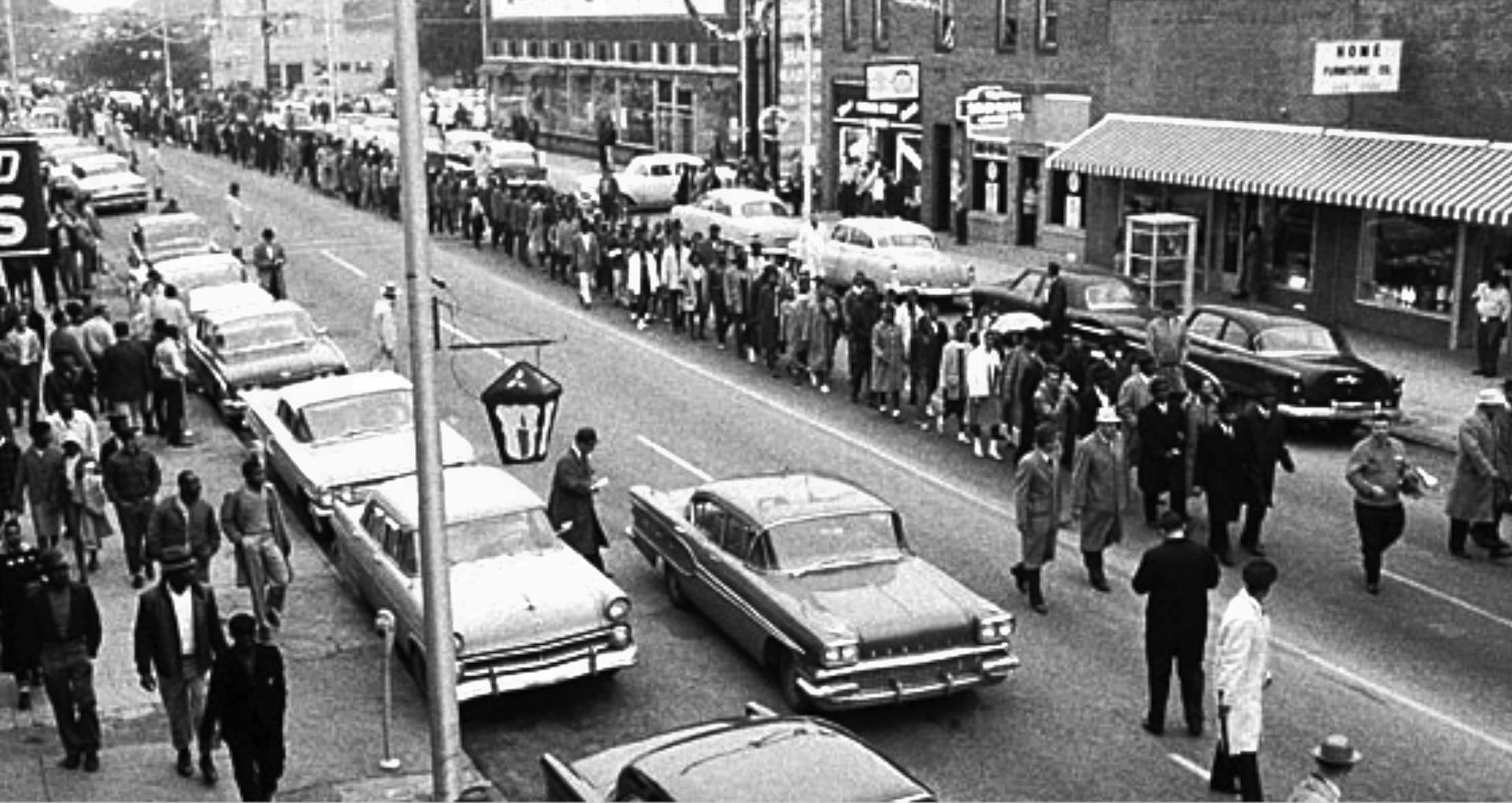

This article from the Arkansas Times explains the history of the sit-in movement that helped desegregate Little Rock. Mr. Branton represented several who were convicted after staging sit-ins at Little Rock restaurants and department stores.

The Court abated the convictions of the petitioners in their respective state courts, and reasoned as follows:

Far from finding a bar to the application of the rule where a state statute is involved, we find that our construction of the effect of the Civil Rights Act is more than statutory. It is required by the Supremacy Clause of the Constitution. Future state prosecutions under the Act being unconstitutional and there being no saving clause in the Act itself, convictions for pre-enactment violations would be equally unconstitutional and abatement necessarily follows.

Nor do we find persuasive reasons for imputing to the Congress an intent to insulate such prosecutions. As we have said, Congress, as well as the two Presidents who recommended the legislation, clearly intended to eradicate an unhappy chapter in our history. The peaceful conduct for which petitioners were prosecuted was on behalf of a principle since embodied in the law of the land. The convictions were based on the theory that the rights of a property owner had been violated. However, the supposed right to discriminate on the basis of race, at least in covered establishments, was nullified by the statute. Under such circumstances the actionable nature of the acts in question must be viewed in the light of the statute and its legislative purpose.

Id. at 315-16, 85 S. Ct. at 391, 13 L. Ed. 2d at 307 (citations omitted). The case resulted in 3,000 similar cases being dismissed nationwide.

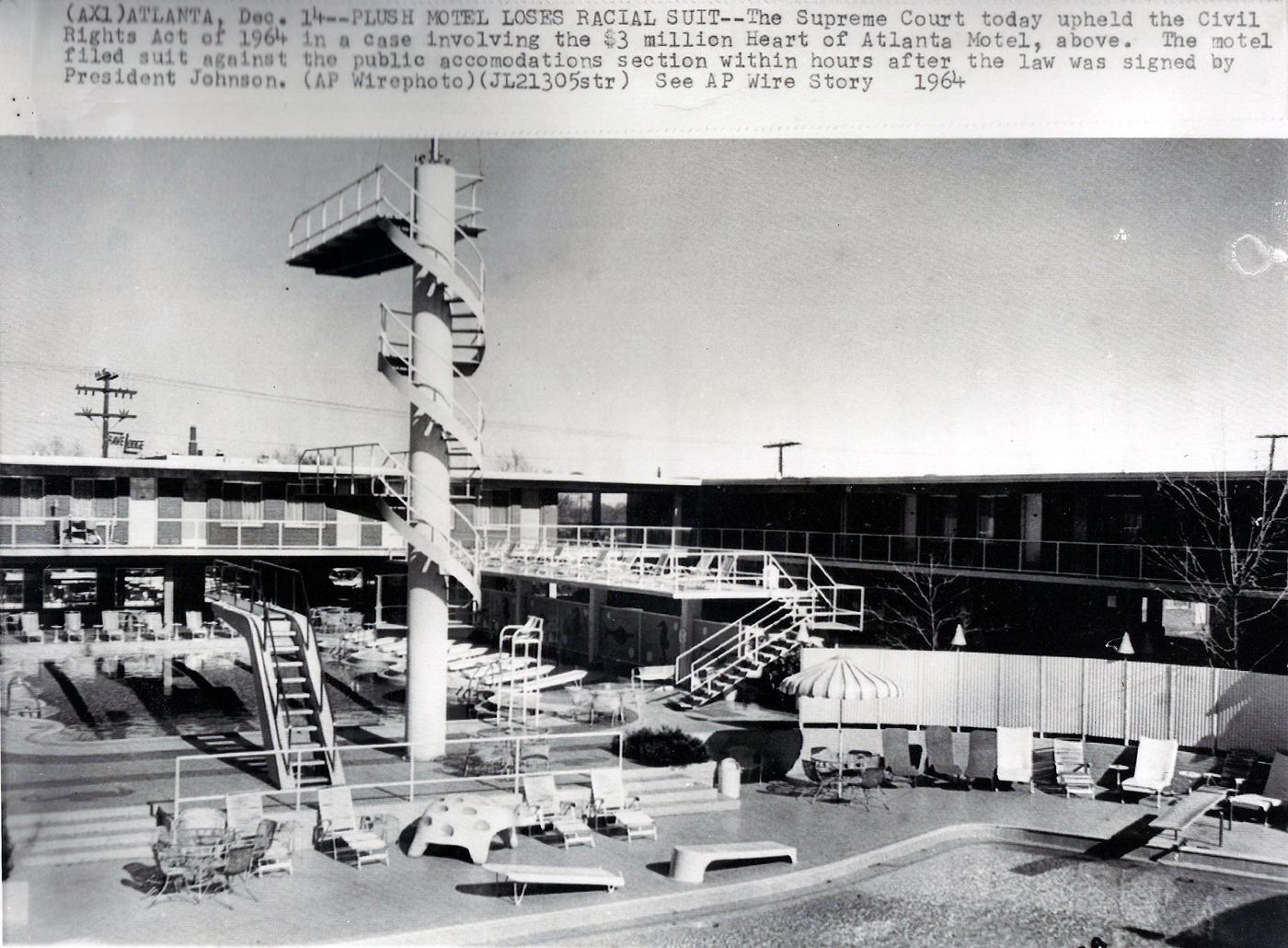

Another example of the Civil Rights Act hastening the end of segregation laws occurred on December 14, 1964 when the U.S. Supreme Court issued a pair of opinions outlawing discrimination in public accommodations. See Heart of Atlanta Motel, Inc. v. United States, 379 U.S. 241, 85 S. Ct. 348, 13 L. Ed. 2d 258 (1964) and Katzenbach v. McClung, 379 U.S. 294, 85 S. Ct. 377, 13 L. Ed. 2d 290 (1964). Mr. Nabrit, Mr. Greenberg, Ms. Baker-Motley, and Charles L. Black, Jr. on behalf of the LDF filed a brief as an impartial adviser to a court in Katzenbach, supra.

At issue was Ollie's Barbecue, a family-owned restaurant in Birmingham, Alabama who refused to serve African Americans (as they had done since the restaurant opened in 1927) in violation of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Katzenbach, 379 U.S. at 296, 85 S. Ct. at 380, 13 L. Ed. 2d at 293.

This article from al.com talks about the case 50 years after the decision was issued.

The District Court found the Civil Rights Act could not be applied to the restaurant under the 14th Amendment because there was no state action by the the state of Alabama. Id. at 297, 85 S. Ct. at 380, 13 L. Ed. 2d at 294. The District Court also found there was no connection between food purchased and sold in interstate commerce, and Congress' conclusion that discrimination in the restaurant would affect interstate commerce.

The restaurant was located "on a state highway 11 blocks from an interstate. ... In the 12 months preceding the passage of the [Civil Rights] Act, the restaurant purchased locally approximately $150,000 worth of food, ... 46% of which was meat that it bought from a local supplier who had procured it from outside the state." Id. at 296, 85 S. Ct. at 380, 13 L. Ed. 2d at 293.

The United States Supreme Court disagreed. It reasoned Congress has the power to regulate intrastate commerce when these activities affect interstate commerce. Id. at 301-02, 85 S. Ct. at 382-83, 13 L. Ed. 2d at 296-97. The Court further reasoned that "this power extends to activities of retail establishments, including restaurants, which directly or indirectly burden or obstruct interstate commerce." Id. at 302, 85 S. Ct. at 383, 13 L. Ed. 2d at 297. The Court found this applied to the restaurant because it served food that came from out of the state. Id. at 304, 85 S. Ct. at 384, 13 L. Ed. 2d at 298. As for Congress' conclusion that discrimination affects interstate commerce, the Court stated as follows:

Congress has determined for itself that refusals of service to Negroes have imposed burdens both upon the interstate flow of food and upon the movement of products generally. Of course, the mere fact that Congress has said when particular activity shall be deemed to affect commerce does not preclude further examination by this Court. But where we find that the legislators, in light of the facts and testimony before them, have a rational basis for finding a chosen regulatory scheme necessary to the protection of commerce, our investigation is at an end. The only remaining question -- one answered in the affirmative by the court below -- is whether the particular restaurant either serves or offers to serve interstate travelers or serves food a substantial portion of which has moved in interstate commerce.

Id. at 303-04, 85 S. Ct. at 383-84, 13 L. Ed. 2d at 298. Heart of Atlanta Motel, Inc., supra, likewise upheld the constitutionality of the Civil Rights Act as applied to a motel that refused to rent rooms to African Americans despite 75% of its guest coming from out of state. Other pictures, and an interesting story about the motel's owner, are found here.

In early 1965, an effort was made to register African American voters in Alabama. A march from Selma to Montgomery was planned in response to the death of a young African American protestor, Jimmie Lee Jackson, on February 18, 1965. The purpose of the march was to demonstrate the desire of African American citizens to exercise their constitutional right to vote.

This photograph was taken on March 7, 1965. Approximately 60-70 Alabama state troopers and others met approximately 650 African Americans as they crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge in a march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama.

Alabama law enforcement used "tactics ... similar to those recommended for use by the U.S. Army to quell armed rioters in occupied countries" to stop the march. Williams v. Wallace, 240 F. Supp. 100, 105 (M.D. Ala. 1965). This event became known as "bloody Sunday," and was made into a movie called Selma in 2014. Two days later, the marchers would try again as seen below:

This photograph shows marchers turning back in the second unsuccessful march on March 9, 1965.

Before the third march, Mr. Gray, Mr. Nabrit, and others used the Civil Rights Act as a basis in representing Hosea Williams, John Lewis, and Amelia Boynton (and others) in seeking an order from the federal court for the Middle District of Alabama to allow the peaceful, non-violent march from Selma to Montgomery to occur. Id.

The federal judge, Frank M. Johnson, Jr., granted the request, and stated the march "involved nothing more than a peaceful effort on the part of [the African American] citizens to exercise a classic constitutional right; that is, the right to assemble peaceably and to petition one's government for the redress of grievances." Id. at 105. As a result, the judge granted an injunction against the Alabama state officials, which prohibited them from arresting, harassing, threatening, or interfering with the march, or otherwise obstructing or impeding with the peaceful, non-violent efforts of the marchers. Id. at 110.

The third March occurred from March 21-24, 1965 with the protection of the Alabama National Guard under federal command, the FBI, and federal marshals. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 was signed by President Lyndon Johnson on August 6, 1965.

Other contexts in which the Civil Rights Act ended discriminatory practices are listed here, which were accomplished through the efforts of many of the attorneys listed above.

While the list of great barristers mentioned herein is not comprehensive, the efforts of these important Civil Rights attorneys exemplify what it takes to be successful in life. While bad things (legal decisions and otherwise) happened to their clients, these attorneys never gave up. I'm sure in their day they were told among other things that "nothing would ever change," that their efforts "wouldn't get them anywhere," and much, much worse. Not only did they get somewhere, they changed modern Constitutional law as we know it today in several different respects. They serve as shining examples of what can be accomplished with a law license, and that one attorney can make a difference.

![The restaurant was located "on a state highway 11 blocks from an interstate. ... In the 12 months preceding the passage of the [Civil Rights] Act, the restaurant purchased locally approximately $150,000 worth of food, ... 46% of which was meat that …](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/517f0942e4b0d875cbc6d53f/1516650625623-5EQ4JEN1N664922K6CJB/59315.jpg)